Odovtos-International Journal of Dental Sciences (Odovtos-Int. J. Dent. Sc.), Online First, 2025. ISSN: 2215-3411

https://doi.org/10.15517/at7ad013

https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/Odontos

CLINICAL RESEARCH:

Regional Disparities in the Prevalence and Severity of Early Childhood Caries Among Preschoolers Living in Poverty in Costa Rica

Desigualdades regionales en la prevalencia y severidad de la caries de la primera infancia en preescolares

en condición de pobreza en Costa Rica

Adrián Gómez-Fernández DDS, Mag¹ https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2132-0137

Katherine Molina-Chaves DDS, Mag¹ https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7715-4778

Sylvia Gudiño-Fernández DDS, Mag¹ https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8746-1066

¹Master's Program in Pediatric Dentistry, Faculty of Dentistry, Postgraduate Studies System, University of Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica.

Correspondence to: Adrián Gómez-Fernández - ADRIAN.GOMEZFERNANDEZ@ucr.ac.cr

Received: 27-VII-2025 Accepted: 14-VIII-2025

ABSTRACT: Early childhood dental caries remains a major public health concern, especially among populations affected by socioeconomic and geographic disparities. In Costa Rica, persistent regional inequalities may influence the burden and severity of this condition. To analyze regional disparities in the prevalence and severity of dental caries among Costa Rican preschool children living in poverty. A secondary analysis was conducted using data from a descriptive, cross-sectional study carried out in 2013. The national sample included 803 children under 81 months of age enrolled in government-run centers for early childhood care and nutrition (CEN-CINAI). Clinical assessments were performed using the ICDAS system. Descriptive statistics and regional comparison tests were applied. The national caries prevalence in Costa Rica was 84.81%. Significant regional differences in severity were observed, with higher averages of affected teeth and surfaces in the Chorotega and Brunca regions. While incipient lesions (ICDAS 1-2) were most frequent, a substantial burden of moderate and severe lesions (ICDAS 3-6) was also detected, particularly in rural areas with greater structural vulnerability and limited access to oral health services.The high prevalence of dental caries and the documented regional inequalities highlight the need to strengthen prevention, early diagnosis, and timely treatment. Integrating a territorial approach into oral health policy-through early detection, preventive interventions, caregiver education, and mobile dental services-may help reduce disparities and improve pediatric oral health outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Dental caries; Oral health; Preschool children; Health inequities; Regional disparities; Costa Rica; Poverty.

RESUMEN: La caries dental en la infancia temprana sigue siendo un problema importante de salud pública, especialmente en poblaciones afectadas por desigualdades socioeconómicas y geográficas. En Costa Rica, persisten desigualdades regionales que podrían influir en la carga y severidad de esta enfermedad. Analizar la prevalencia y severidad de caries dental en preescolares costarricenses en condición de pobreza, identificando desigualdades regionales. Se realizó un análisis secundario de datos provenientes de un estudio descriptivo, transversal, llevado a cabo en 2013, con una muestra nacional de 803 niños menores de 81 meses, matriculados en centros públicos de atención y nutrición infantil (CEN-CINAI). Las evaluaciones clínicas se realizaron mediante el sistema ICDAS. Se aplicaron estadísticas descriptivas y pruebas de comparación regional. La prevalencia nacional de caries fue del 84,81 %. Se identificaron diferencias regionales significativas en la severidad de la enfermedad, con mayores promedios de dientes y superficies afectadas en las regiones Chorotega y Brunca. Aunque predominaban las lesiones incipientes (ICDAS 1-2), se evidenció una carga considerable de lesiones moderadas y severas (ICDAS 3-6), especialmente en zonas rurales con mayor vulnerabilidad estructural y acceso limitado a servicios odontológicos. La alta prevalencia de caries y las desigualdades regionales evidenciadas destacan la necesidad de fortalecer la prevención, el diagnóstico precoz y la atención oportuna. Incorporar un enfoque territorial en las políticas de salud bucodental, mediante estrategias de detección temprana, intervenciones preventivas, educación a cuidadores y servicios móviles, puede ayudar a reducir desigualdades y mejorar los resultados en salud bucal infantil.

PALABRAS CLAVE: Caries dental; Salud bucal; Niños preescolares; Inequidades en salud; Desigualdades regionales; Costa Rica; Pobreza.

Introduction

Territorial inequalities in early childhood oral health remain a persistent public health challenge, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (1). According to the Global Burden of Disease Study, untreated dental caries in primary teeth ranks among the most prevalent conditions affecting children and shows significant regional disparities worldwide (2).

Dental caries, the most common chronic disease in childhood, disproportionately affects children living in poverty due to structural barriers to care (3). In Costa Rica, these challenges are evident among preschool populations, who face overlapping social and territorial vulnerabilities, including limited access to oral health services, low caregiver education, and persistent poverty (4).

Although comprehensive childcare policies have been implemented, the prevalence of dental caries remains considerably high. This situation is partly explained by the limited integration of oral health services into primary care (5), combined with social and territorial determinants such as socioeconomic status, caregiver education, service availability, hygiene practices, and dietary habits-all of which vary between urban and rural areas and generate distinct risk profiles (6,7). These factors play a decisive role in the global distribution of oral diseases in early childhood (8,9). A multicenter study conducted in Latin America among children aged 1-3 years identified Costa Rica as one of the countries with the earliest introduction of sugars in liquid form (10).

Costa Rica has marked regional disparities in economic development, infrastructure, and access to health services, all of which may influence the burden of early childhood caries (ECC) (11,12). Internationally, such geographic inequalities have been shown to affect various health outcomes, including oral health (13). However, national data are often reported in aggregate form, limiting the ability to detect specific territorial patterns and design context-sensitive public policies (14,15). ECC has also been shown to negatively affect the quality of life of both children and their families. A multicenter study in 10 Latin American countries reported a mean Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS) score of 6.0 (±12.0) among preschool children aged 1-3 years (16).

The Education and Nutrition Centers and the Comprehensive Child Nutrition and Care Centers (Centros de Educación y Nutrición and Centros Infantiles de Nutrición y Atención Integral – CEN-CINAI), operated by the Ministry of Health of Costa Rica, provide a strategic platform for reducing oral health inequalities. These centers serve children from low-income families throughout the country and thus represent a valuable source for analyzing regional differences and informing equitable prevention and care strategies (17). Unfortunately, most available studies do not disaggregate data by region, which limits the identification of territorial patterns in caries distribution (18).

Moreover, in Costa Rica, most studies on ECC were published between 2000 and 2010, with a primary focus on risk factors. These studies addressed aspects such as breastfeeding, bottle-feeding, consumption of sugars in liquid and solid form, oral hygiene, family environment, and colonization by Streptococcus mutans in high-risk populations (19-21). However, only one study examined the prevalence of ECC among Costa Rican preschoolers; it was conducted in the metropolitan area and included 414 infants aged 12-24 months. This study also considered non-cavitated lesions and estimated a prevalence of 36%, with an average of 4.1 ± 3.6 affected teeth (22).

While previous analyses of the 2013 national oral health study of preschool children enrolled in CEN-CINAI centers have described overall prevalence and sociodemographic characteristics, regional disparities in caries burden and severity have not yet been explored. Therefore, the present study aimed to examine regional inequalities in the prevalence and severity of dental caries among Costa Rican preschool children living in poverty. The analysis is based on clinical data collected from CEN-CINAI centers, using the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS) (23) and the regional classification established by Costa Rica’s Ministry of National Planning and Economic Policy (Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica-MIDEPLAN) (24).

This study contributes updated evidence on territorial disparities in early childhood oral health and underscores the need to incorporate a geographic perspective into both epidemiological surveillance and public health policy. Ensuring the right to oral health for vulnerable populations requires recognizing how structural and social inequalities manifest geographically and addressing them through locally adapted strategies (25). Aggregated national data may obscure critical regional variations, limiting the effectiveness of targeted interventions (18).

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

A secondary analysis was conducted using data from a descriptive, cross-sectional investigation carried out between March and June 2013. While the original study assessed the national prevalence and severity of dental caries, the present analysis focuses specifically on identifying regional disparities in caries prevalence and severity among Costa Rican preschool children under 81 months of age living in poverty.

The population analyzed consisted of children enrolled in CEN-CINAI centers-public institutions coordinated by the Ministry of Health of Costa Rica that operate in communities with high levels of social vulnerability. All participants met institutional eligibility criteria based on socioeconomic disadvantage.

Sampling and Geographic Distribution

The original sample was selected using a stratified two-stage sampling design, employing the probability proportional to size (PPS) method, where centers with a higher number of enrolled children had a greater probability of being selected. The CEN-CINAI centers served as the primary sampling units, and only those with at least 15 enrolled children under 81 months of age were considered for inclusion.

Within each selected center, up to 25 children were chosen using systematic sampling. If the center had 25 or fewer eligible children, all were included.

The final sample consisted of 803 children from 40 CEN-CINAI centers distributed across six planning regions, as defined by the Ministry of National Planning and Economic Policy (MIDEPLAN): Central (17 centers), Chorotega (8), Huetar Atlantic (4), Huetar North (4), Central Pacific (4), and Brunca (3). This sampling approach ensured representativeness across both urban and rural areas with diverse structural conditions and access to health services.

For this analysis, clinical and demographic data were categorized by the region in which each CEN-CINAI center was located, enabling geographic comparisons in the prevalence and severity of early childhood caries.

Clinical Examination

Clinical examinations were conducted onsite at the participating CEN-CINAI centers, using portable dental units equipped with individual lights, air compressors, and mobile chairs. Standard diagnostic instruments included a #5 dental mirror, a WHO 11.5 periodontal probe with a ball tip (used in cases of diagnostic uncertainty), and a headlamp.

Each clinical team comprised a calibrated examiner, an assistant, and a person responsible for recording data. Prior to examination, all participants underwent supervised toothbrushing to standardize oral conditions. Standard biosafety protocols were followed, including the use of gloves, face masks, eye protection, and proper sterilization of instruments between patients.

Eight trained examiners conducted the assessments in accordance with international standards and under the supervision of certified experts in the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS). Calibration was verified through a pilot study involving 30 children not included in the main sample and was reinforced throughout data collection. Inter- and intra-examiner agreement, assessed using Cohen’s kappa coefficients, ranged from 0.80 to 0.93, indicating strong diagnostic reliability.

Each tooth surface was first examined under wet conditions and then re-evaluated after drying with compressed air or sterile gauze. Carious lesions were recorded using ICDAS criteria (26), which allow for the detection of both early non-cavitated and advanced cavitated lesions with higher sensitivity than traditional indices.

Lesions were documented using a standardized form for primary dentition and classified by clinical severity as follows:

- Initial lesions: ICDAS 1 (visible only after drying) and ICDAS 2 (visible on a wet surface)

- Moderate lesions: ICDAS 3 (localized enamel microcavity) and ICDAS 4 (underlying dark shadow)

- Severe lesions: ICDAS 5 (distinct cavity with visible dentin) and ICDAS 6 (extensive cavity with exposed dentin)

Statistical Analysis

A comparative analysis of caries prevalence and severity by geographic region was conducted. Descriptive statistics-including absolute frequencies, percentages, and measures of central tendency-were used to report caries prevalence, lesion severity, and dental conditions such as restorations and extractions by region.

Differences in proportions between regions were assessed using the chi-square test. Variations in lesion severity and in the average number of affected teeth or surfaces per child were analyzed using one-way ANOVA or the Kruskal-Wallis test, depending on the distribution of the data (parametric or non-parametric). The normality of continuous variables was evaluated using the Shapiro-Wilk test. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed using SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Ethical Considerations

The original study protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of the University of Costa Rica (approval number VI-3058-2012). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or legal guardians of all participants prior to clinical examinations.

This secondary analysis was conducted using fully anonymized data with no personal identifiers, ensuring participant confidentiality. The study complies with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human participants.

Results

A total of 803 Costa Rican preschool children under 81 months of age enrolled in CEN-CINAI centers were included in the analysis. The national mean age was 50.37±12.6 months, with a nearly equal gender distribution (51.10% girls and 48.90% boys). By region, the mean age ranged from 47.07 to 56.42 months.

Regarding oral health status, 84.81% of children presented with at least one carious lesion, 24.03% had restored teeth, and 8.09% had experienced tooth loss due to caries. In contrast, only 12.83% of the children exhibited completely healthy primary dentition, with no lesions, restorations, or extractions.

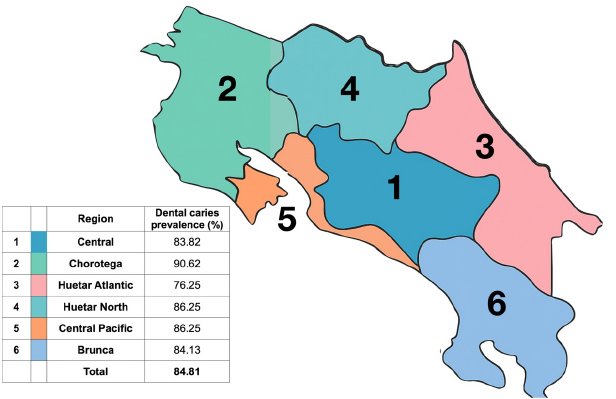

Sociodemographic characteristics and clinical findings varied across regions, particularly in oral health indicators, which are described in detail in the following sections (Table 1). Figure 1 shows Costa Rica’s six planning regions and their corresponding caries prevalence, illustrating marked regional disparities that highlight the need for tailored public health interventions.

Dental caries prevalence exceeded 75% in all six regions, a threshold considered clinically significant in preschool populations. Estimates were based on the ICDAS II system (Table 2). The highest prevalence was observed in Chorotega (90.63%; 95% CI [confidence interval]: 86.11-95.14%), followed by Huetar North and Central Pacific regions (both 86.25%; 95% CI: 78.75-93.75%). Brunca and Central regions showed similar values (84.13% and 83.82%, respectively), and the lowest prevalence was reported in the Huetar Atlantic region (76.25%; 95% CI: 66.25-85.01%). National prevalence was 84.81% (95% CI: 82.44-87.41%).

Although Huetar North and Central Pacific regions had identical prevalence rates, the mean number of decayed teeth per child was higher in the Huetar North region (5.84 vs. 4.88), indicating a greater clinical burden.

The mean number of decayed teeth per child differed significantly across regions (ANOVA, p=0.0023). The highest averages were found in Chorotega (6.44), Huetar North (5.84), and Brunca (5.13). Huetar Atlantic reported both the lowest prevalence and the lowest mean number of decayed teeth (4.01). However, differences in prevalence between regions were not statistically significant (chi-square test, p=0.0998).

Regarding lesion severity, the distribution of children by the number of teeth affected by moderate to severe carious lesions (ICDAS codes 3-6) varied across regions (Table 3). Nationally, 15.07% of children had no advanced lesions, while 38.73% presented with seven or more affected teeth.

The regions with the highest proportion of children with ≥7 moderate or severe lesions were Huetar North (47.50%), Chorotega (44.38%), Central (38.53%), and Brunca (36.51%), indicating a greater burden of advanced caries in these territories. Conversely, the Huetar Atlantic region had the highest percentage of children without advanced lesions (23.75%) and the lowest proportion with high lesion severity (25.00%).

The average distribution of tooth surfaces with carious lesions revealed regional variations according to ICDAS severity codes (Table 4). Nationally, the most common lesions were ICDAS code 2 (incipient lesions visible on a wet surface), with an average of 5.58 affected surfaces per child, and code 6 (extensive cavities), with 1.44 surfaces.

For early-stage lesions, the Central region showed the highest mean for code 1 (0.88 surfaces), above the national average of 0.50. Code 2 was most frequent in Huetar North (6.98), followed by the Central region (6.06), both exceeding the national mean.

Among moderate lesions, code 3 was most prevalent in Brunca (0.71 surfaces), while code 4 reached its highest value in Chorotega (0.89); both were above the national averages of 0.60 and 0.52, respectively.

Regarding severe lesions, Chorotega reported the highest averages for codes 5 (2.79) and 6 (2.39). However, Brunca surpassed Chorotega in code 6 lesions, with a mean of 3.74 affected surfaces per child, indicating a higher burden of extensive cavitated lesions in that region.

When carious lesions were grouped by clinical severity (Table 4), mild lesions (ICDAS codes 1 and 2) were found to be the most frequent in all regions, with a national average of 6.08 affected surfaces per child. Moderate lesions (codes 3 and 4) averaged 1.11 surfaces, while severe lesions (codes 5 and 6) averaged 2.86 surfaces per child.

At the regional level, the Huetar North region reported the highest average of mild lesions (7.16), followed by Central region (6.94) and Chorotega (6.26). For severe lesions, Chorotega showed the highest average (5.18), while the Huetar Atlantic region had the lowest averages for both mild (3.59) and severe lesions (1.43).

This pattern is demonstrated in the distribution by ICDAS code (Table 4), where code 2 (incipient lesion) was the most frequent nationally, followed by code 6 (extensive cavity), suggesting the simultaneous presence of both early and advanced disease in the population.

According to the cumulative data presented in Table 5 (ICDAS codes 1-6), the national average was 8.97 affected surfaces per child (SD=9.51). The Chorotega region had the highest average (11.58), followed by the Brunca region (9.97), while the Huetar Atlantic region showed the lowest average (5.26).

When considering moderate and severe lesions only (ICDAS codes 3-6), the national average was 3.54 surfaces per child (SD=6.56). Chorotega (6.00) and Brunca (6.02) had the highest values, indicating a greater burden of advanced disease compared with other regions.

Table 1. Sociodemographic Characteristics and Dental Conditions by Region Among Costa Rican Preschool Children Under 81 Months of Age Living in Poverty.

|

Region |

Participants (n) |

Mean Age (months) ± SD |

Girls (%) |

Boys (%) |

Children with Carious Lesions (%) |

Children with Restored Teeth (%) |

Children with Teeth Lost Due to Caries (%) |

Children with All Teeth Sound (%) |

|

Central |

340 |

47.07 ± 13.06 |

50.59 |

49.41 |

83.82 |

17.06 |

6.18 |

15.0 |

|

Chorotega |

160 |

51.11 ± 12.91 |

46.88 |

53.12 |

90.62 |

25.62 |

11.25 |

8.13 |

|

Huetar Atlantic |

80 |

53.14 ± 9.05 |

62.50 |

37.50 |

76.25 |

17.50 |

5.00 |

21.25 |

|

Huetar North |

80 |

56.42 ± 10.88 |

47.50 |

52.50 |

86.25 |

45.0 |

7.50 |

7.50 |

|

Central Pacific |

80 |

51.40 ± 11.63 |

52.50 |

47.50 |

86.25 |

28.75 |

8.75 |

10.0 |

|

Brunca |

63 |

53.81 ± 12.13 |

52.38 |

47.62 |

84.13 |

33.33 |

14.29 |

12.70 |

|

Total |

803 |

50.37 ± 12.64 |

51.10 |

48.90 |

84.81 |

24.03 |

8.09 |

12.83 |

Figure 1. Regional distribution of dental caries prevalence (%) among Costa Rican preschool children under 81 months of age living in poverty. The map displays Costa Rica’s six planning regions and their respective caries prevalence, based on ICDAS criteria.

Table 2. Comparison of Regional Caries Prevalence, 95% Confidence Intervals, and Mean Number of Decayed Teeth Among Costa Rican Preschool Children Under 81 Months of Age Living in Poverty.

|

Region |

Participants (n) |

Children with Caries (n) |

Prevalence (%) |

95% CI |

Mean De-cayed Teeth |

SD |

|

Central |

340 |

285 |

83.82 |

79.71–87.65% |

5.60 |

4.64 |

|

Chorotega |

160 |

145 |

90.63 |

86.11–95.14% |

6.44 |

4.72 |

|

Huetar Atlantic |

80 |

61 |

76.25 |

66.25–85.01% |

4.01 |

3.94 |

|

Huetar North |

80 |

69 |

86.25 |

78.75–93.75% |

5.84 |

4.33 |

|

Central Pacific |

80 |

69 |

86.25 |

78.75–93.75% |

4.88 |

3.91 |

|

Brunca |

63 |

53 |

84.13 |

74.60–92.06% |

5.13 |

4.62 |

|

Total |

803 |

682 |

84.81 |

82.44–87.41% |

- |

- |

Note: SD = Standard deviation. CI = Confidence interval.

Table 3. Severity of Dental Caries According to the Number of Teeth with Moderate or Severe Lesions (ICDAS 3-6), by Region.

|

Region |

No Teeth with Le-sions (%) |

1–3 Teeth with Le-sions (%) |

4–6 Teeth with Le-sions (%) |

7 or More Teeth with Lesions (%) |

|

Central |

16.18 |

22.65 |

22.65 |

38.53 |

|

Chorotega |

9.38 |

21.88 |

24.38 |

44.38 |

|

Huetar Atlantic |

23.75 |

32.5 |

18.75 |

25.0 |

|

Huetar North |

13.75 |

22.5 |

16.25 |

47.50 |

|

Central Pacific |

13.75 |

33.75 |

17.50 |

35.0 |

|

Brunca |

15.87 |

33.33 |

14.29 |

36.51 |

|

Total |

15.07 |

25.40 |

20.80 |

38.73 |

Note: Only tooth surfaces with moderate or severe carious lesions (ICDAS codes 3-6) were considered.

Table 4. Mean Number of Tooth Surfaces with Carious Lesions per Child by ICDAS Code (1-6) and Region.

|

Region |

Code 1 |

Code 2 |

Code 3 |

Code 4 |

Code 5 |

Code 6 |

|

Central |

0.88 |

6.06 |

0.68 |

0.44 |

1.16 |

0.88 |

|

Chorotega |

0.37 |

5.89 |

0.67 |

0.89 |

2.79 |

2.39 |

|

Huetar Atlantic |

0.42 |

3.17 |

0.26 |

0.45 |

1.06 |

0.37 |

|

Huetar North |

0.18 |

6.98 |

0.61 |

0.29 |

0.59 |

1.35 |

|

Central Pacific |

0.0 |

5.01 |

0.33 |

0.33 |

0.80 |

1.28 |

|

Brunca |

0.02 |

4.37 |

0.71 |

0.58 |

1.66 |

3.74 |

|

Total |

0.50 |

5.58 |

0.60 |

0.52 |

1.42 |

1.44 |

Note: Affected surfaces were assessed using the ICDAS criteria.

Table 5. Mean Number of Tooth Surfaces with Carious Lesions per Child Considering All Lesions (ICDAS Codes 1-6) and Only Moderate to Severe Lesions (ICDAS Codes 3-6) by Region.

|

Region |

Participants (n) |

Mean Surfaces with Lesions (ICDAS 1-6) |

SD |

Mean Surfaces with Lesions (ICDAS 3-6) |

SD |

|

Central |

340 |

8.85 |

9.17 |

2.78 |

5.15 |

|

Chorotega |

160 |

11.58 |

11.43 |

6.0 |

8.81 |

|

Huetar Atlantic |

80 |

5.26 |

6.0 |

1.96 |

3.94 |

|

Huetar North |

80 |

9.08 |

8.16 |

2.58 |

4.76 |

|

Central Pacific |

80 |

7.03 |

7.28 |

2.49 |

5.27 |

|

Brunca |

63 |

9.97 |

11.68 |

6.02 |

9.91 |

|

Total |

803 |

8.97 |

9.51 |

3.54 |

6.56 |

Note: ICDAS codes 1-6 include all surfaces with carious lesions. ICDAS codes 3–6 include only moderate and severe lesions. SD=Standard deviation.

Discussion

This study revealed a high national prevalence of dental caries (84.81%) among Costa Rican preschool children under 81 months of age living in poverty. This finding aligns with international evidence indicating a greater caries burden in socially vulnerable populations from early childhood (27,28). Despite national efforts to promote comprehensive childcare, significant gaps persist in prevention and access to timely dental treatment (5).

Marked regional disparities were identified, confirming the existence of geographic inequalities in oral health. The Chorotega region reported the highest caries prevalence (90.63%) and the highest number of advanced lesions (ICDAS codes 5-6), followed by Brunca-regions where access to restorative care remains limited for low-income families (29). These patterns reflect the impact of structural determinants, including unequal distribution of oral health professionals, educational inequalities, and restricted access to services (8,11).

The surface-based analysis of lesion severity provided a more nuanced view of disease progression. Incipient lesions (ICDAS 1-2) were the most frequent, particularly in Central and Huetar North regions, highlighting an opportunity for early, non-invasive interventions. At the national level, moderate and severe lesions (ICDAS 3-6) affected an average of 3.54 surfaces per child-almost 60% fewer than the overall average of 8.97-suggesting that a significant proportion of disease is still in early stages and potentially reversible. However, regions like Brunca and Chorotega showed a higher average of extensive cavities, indicating significant care needs and underlying clinical burdens (30).

Despite similar prevalence rates in regions like Huetar North and Central Pacific (86.25%), differences in the mean number of decayed teeth (5.84 vs. 4.88) suggest varying levels of clinical severity. Furthermore, more than one-third of the children (38.7%) had seven or more teeth affected by moderate or severe caries, with the highest burden in the Huetar North, Chorotega, and Central regions, which face greater risks of pain, infection, and long-term consequences for permanent dentition (31).

These findings are consistent with Latin American studies that have reported negative impacts of early childhood caries on quality of life (16,32). Similar trends have been observed in Costa Rican adolescents from vulnerable populations, who also present a dual burden of incipient and advanced lesions (33).

From a public health perspective, the data underscore the need for territorial prioritization in oral health policies. While progress has been observed in urban settings, rural and socioeconomically disadvantaged regions continue to experience limited coverage and weaker program implementation (34). School-based programs in high-risk areas, such as the Carmen Lyra School in San José, have demonstrated promising results: a caries prevalence of 59.7% and predominance of early-stage lesions among children who received sustained dental care (35).

International experiences further emphasize the importance of multisectoral strategies to reduce territorial inequities (36). In oral health, effective programs must combine universal measures with targeted interventions. The Brasil Sorridente program has shown that access can be expanded through mobile dental units, integration with primary care, and community-adapted delivery models (37) strategies that could be adapted to Costa Rican regions such as Chorotega, Brunca, and Huetar North.

The higher disease burden in certain regions may be associated with high sugar consumption, low fluoride exposure, and limited access to oral health services. Addressing these factors requires intersectoral collaboration, sustained investment in prevention, and actions such as expanding fluoride varnish programs (38), educating caregivers, and deploying mobile dental clinics (39).

Although the data analyzed were collected in 2013, they provide a valuable baseline for monitoring geographic disparities in preschool oral health. The absence of more recent studies with regional disaggregation limits the evaluation of public policy impact (40).

To improve equity in oral health care, it is essential to conduct periodic national surveys with regional and social stratification, incorporating both clinical indicators and contextual determinants. The present analysis contributes key evidence for guiding national oral health planning and reinforcing the prioritization of territorial equity in policies targeting early childhood.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the data were collected in 2013; although they provide a valuable baseline, they may not fully represent the current epidemiological situation. Second, the cross-sectional design limits causal inference. Third, although regional disaggregation allowed for the identification of geographic disparities, the use of aggregate data from CEN-CINAI centers may obscure intra-regional differences or exclude children not enrolled in the program. Nevertheless, the study provides robust and regionally disaggregated clinical data that remain highly relevant for public health planning.

Conclusions

This study revealed a high prevalence of early childhood caries among Costa Rican preschoolers living in poverty, with marked regional disparities in severity and clinical burden. Although early-stage lesions were the most common, a considerable proportion of children had multiple moderate or severe lesions, reflecting substantial treatment needs.

The Chorotega and Brunca regions recorded the highest levels of clinical severity, underscoring the urgent need for targeted public health interventions. Strategies such as fluoride varnish application, caregiver education, mobile dental clinics, and action on structural determinants are essential to reduce these inequalities.

The use of the ICDAS system enabled a detailed characterization of lesion progression, providing valuable evidence to guide preventive and restorative planning from a public health perspective.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION STATEMENT: Conceptualization and design: A.G.F. and S.G.F.; Literature review: A.G.F.; Methodology and validation: A.G.F. and S.G.F.; Formal analysis: A.G.F.; Research and data collection: A.G.F., K.M.C. and S.G.F.; Resources: A.G.F. and S.G.F.; Data analysis and interpretation: A.G.F.; Original draft preparation and writing: A.G.F.; Writing, review, and editing: A.G.F., S.G.F., and K.M.C.; Supervision: S.G.F.; Project administration: A.G.F. and S.G.F.; Funding acquisition: Not applicable for this study.

Acknowledgments: Special thanks are extended to the team of general and pediatric dentists who conducted the clinical examinations during the national oral health survey of Costa Rican preschoolers. The authors acknowledge the institutional support provided by the University of Costa Rica and the College of Dental Surgeons of Costa Rica, which was essential to the implementation of the original study. We are especially grateful to the CEN-CINAI centers, their staff, and the participating families for their collaboration and trust throughout the research process.

References

1. Watt R.G., Daly B., Allison P., et al. Ending the neglect of global oral health: time for radical action. Lancet. 2019; 394 (10194): 261-272. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31133-X

2. Wen P.Y.F., Chen M.X., Zhong Y.J., Dong Q.Q., Wong H.M. Global burden and inequality of dental caries, 1990 to 2019. J Dent Res. 2022; 101 (4): 392-399. doi:10.1177/00220345211056247

3. Petersen P.E. Challenges to improvement of oral health in the 21st century--the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Int Dent J. 2004; 54 (6 Suppl 1): 329-343. doi:10.1111/j.1875-595x.2004.tb00009.x

4. López Torres A.C., Bermúdez Mora G.A. Salud bucal costarricense: análisis de la situación de los últimos años. Odontol Sanmarquina. 2020; 23 (3): 341-349. doi:10.15381/os.v23i3.18403

5. Prasad M., Manjunath C., Murthy A.K., Sampath A., Jaiswal S., Mohapatra A. Integration of oral health into primary health care: a systematic review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019; 8 (6): 1838-1845. doi:10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_286_19

6. Watt R.G., Listl S., Peres M., Heilmann A. Social inequalities in oral health: from evidence to action. London: International Centre for Oral Health Inequalities Research & Policy; 2015 [Internet]. Available from: https://media.news.health.ufl.edu/misc/cod-oralhealth/docs/posts_frontpage/SocialInequalities.pdf

7. Peres M.A., Macpherson L.M.D., Weyant R.J., et al. Oral diseases: a global public health challenge [published correction appears in Lancet. 2019 Sep 21; 394 (10203): 1010. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32079-3.]. Lancet. 2019;394(10194):249-260.doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31146-8

8. Petersen P.E., Bourgeois D., Ogawa H., Estupinan-Day S., Ndiaye C. The global burden of oral diseases and risks to oral health. Bull World Health Organ. 2005; 83 (9): 661-669.

9. Frencken J.E., Sharma P., Stenhouse L., Green D., Laverty D., Dietrich T. Global epidemiology of dental caries and severe periodontitis - a comprehensive review. J Clin Periodontol. 2017; 44 Suppl 18: S94-S105. doi:10.1111/jcpe.12677

10. Feldens C.A., Alvarez L., Acevedo A.M., et al. Early-life sugar consumption and breastfeeding practices: a multicenter initiative in Latin America. Braz Oral Res. 2023; 37: e104. doi:10.1590/1807-3107bor-2023.vol37.0104

11. Programa Estado de la Nación. Informe Estado de la Nación 2024: Capítulo 2- Bienestar social y equidad. San José (CR): Consejo Nacional de Rectores; 2024. p. 76-103. Available from: https://repositorio.conare.ac.cr/server/api/core/bitstreams/92ab73f3-1cfe-4327-9717-060d2db111af/content

12. Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Censos (INEC). Encuesta Nacional de Hogares: informe de resultados. San José: INEC; 2024. Available from: https://admin.inec.cr/sites/default/files/2024-10/reenaho2024.pdf.pdf

13. Marmot M., Friel S., Bell R., Houweling T.A., Taylor S.; Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Lancet. 2008; 372 (9650): 1661-1669. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61690-6

14. Lorenzo S., Apelo F., Olmos P., Massa F., Laporta P., Zubiaguirre T. Salud bucal como derecho ciudadano y su relación con la prevención de enfermedades no transmisibles. Univ Diálogo. 2022; 12 (2): 101-116. doi:10.15359/udre.12-2.5

15. Pacheco Jiménez J.F. Desigualdades territoriales en el acceso a los servicios de salud pública (CCSS). Informe Estado de la Nación en Desarrollo Humano Sostenible 2024. San José (CR): Programa Estado de la Nación; 2024. Available from: https://repositorio.conare.ac.cr/server/api/core/bitstreams/0c7aaebe-4377-4cd4-8a80-150c1065c0c4/content

16. Paiva S.M., Martins L.P., Bittencourt J.M., et al. Impact on oral health-related quality of life in infants: multicenter study in Latin American countries. Braz Dent J. 2022; 33 (2): 61-67. doi:10.1590/0103-6440202204929

17. Ministerio de Salud de Costa Rica. Manual operativo de los CEN-CINAI. San José: Ministerio de Salud; 2020. Available from: https://www.cen-cinai.go.cr/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Manual_Operativo_jornadas_Vespertina_y_Nocturna.pdf

18. Kassebaum N.J., Smith A.G.C., Bernabé E., et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence, incidence, and disability-adjusted life years for oral conditions for 195 countries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of diseases, injuries, and risk factors. J Dent Res. 2017; 96 (4): 380-387. doi:10.1177/0022034517693566

19. Gudiño-Fernández S. Lactancia materna, biberón, azúcares en solución y caries de la temprana infancia en el San José urbano. Odovtos - Int J Dent Sc. 2007; 9: 77-88. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4995/499551912016.pdf

20. Gudiño-Fernández S. Higiene oral, entorno familiar, azúcares sólidos, enfermedades respiratorias y caries de la temprana infancia en el área metropolitana de San José-Costa Rica. Odovtos - Int J Dent Sc. 2007; 9: 97-104. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/4995/499551912018.pdf

21. Goldstein R., Gudiño-Fernández S. Riesgos nutricionales e higiénicos asociados a la caries de la temprana infancia en el binomio madre-hijo en el distrito Josefino de Río Azul. Rev Cient Odontol. 2007; 3 (2): 74-80. Available from: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=324227907007

22. Gudiño-Fernández S. Prevalencia y análisis descriptivo del patrón de caries dental en niños costarricenses de 12 a 24 meses. Odovtos - Int J Dent Sc. 2003; 5: 68-75.

23. Dikmen B. ICDAS II criteria (international caries detection and assessment system). J Istanb Univ Fac Dent. 2015; 49 (3): 63-72. doi:10.17096/jiufd.38691

24. Ministerio de Planificación Nacional y Política Económica (MIDEPLAN). Mapa de regiones de Costa Rica. San José (CR): MIDEPLAN; 2023. Available from: https://documentos.mideplan.go.cr/share/s/zCZzjyCaTOSLZWX74BMTOQ

25. Sheiham A., Watt R.G. The common risk factor approach: a rational basis for promoting oral health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2000; 28 (6): 399-406. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0528.2000.028006399.x

26. Ismail A.I., Sohn W., Tellez M., et al. The International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS): an integrated system for measuring dental caries. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2007; 35 (3): 170-178. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0528.2007.00347.x

27. Moynihan P.J., Kelly S.A. Effect on caries of restricting sugars intake: systematic review to inform WHO guidelines. J Dent Res. 2014; 93 (1): 8-18. doi:10.1177/0022034513508954

28. Nath S., Sethi S., Bastos J.L., et al. A global perspective of racial-ethnic inequities in dental caries: protocol of systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022; 19 (3): 1390. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031390

29. Tinanoff N., Baez R.J., Diaz Guillory C., et al. Early childhood caries epidemiology, aetiology, risk assessment, societal burden, management, education, and policy: global perspective. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2019; 29 (3): 238-248. doi:10.1111/ipd.12484

30. Fejerskov O., Nyvad B., Kidd E.A.M. Dental caries: the disease and its clinical management. 3rd ed. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell; 2015. p. 115-160.

31. Casamassimo P.S., Thikkurissy S., Edelstein B.L., Maiorini E. Beyond the dmft: the human and economic cost of early childhood caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009; 140 (6): 650-657. doi:10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0250

32. Peña-Alegre M., Porcel I.N., Mattos-Vela M.A., Villavicencio-Caparó E. Impact of oral conditions on quality of life in Peruvian preschoolers in rural and urban areas. Odovtos - Int J Dent Sc. 2023; 25 (3): 162-173. doi:10.15517/ijds.2023.55835

33. Gudiño-Fernández S., Gómez-Fernández A., Molina-Chaves K., Barahona-Cubillo J., Fantin R., Barboza-Solís C. Prevalence of dental caries among Costa Rican male students aged 12-22 years using ICDAS-II. Odovtos - Int J Dent Sc. 2021; 23 (2):181-195. doi: 10.15517/IJDS.2021.45650

34. Ortiz Magdaleno M. Salud bucal en América Latina: desafíos por afrontar. Rev Latinoam Difus Cient. 2024; 6 (11): 142-156.

35. Ramírez K., Gómez-Fernández A. Dental caries in 12-year-old schoolchildren who participate in a preventive and restorative dentistry program Odovtos - Int J Dent Sc. 2022; 24 (2): 136-144. doi:10.15517/IJDS.2021.47337

36. Maceira D., Brumana L., Aleman J.G. Reducing the equity gap in child health care and health system reforms in Latin America. Int J Equity Health. 2022; 21 (1): 29. doi:10.1186/s12939-021-01617-w

37. Pucca G.A. Jr., Gabriel M., de Araujo M.E., de Almeida F.C. Ten years of a national oral health policy in Brazil: innovation, boldness, and numerous challenges. J Dent Res. 2015; 94 (10): 1333-1337. doi:10.1177/0022034515599979

38. de Sousa F.S.O., Dos Santos A.P.P., Nadanovsky P., Hujoel P., Cunha-Cruz J., de Oliveira B.H. Fluoride varnish and dental caries in preschoolers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Caries Res. 2019; 53 (5): 502-513. doi:10.1159/000499639

39. Kshirsagar M., Dodamani A., Pimpale S., et al. Mobile dental clinics: bringing smiles on wheels. Cureus. 2025;17 (5): e83873. doi:10.7759/cureus.83873

40. Galante M.L., Otálvaro-Castro G.J., Cornejo-Ovalle M.A., Patiño-Lugo D.F., Pischel N., Giraldes A.I., Carrer F.C. de A. Oral health policy in Latin America: challenges for better implementation. EJDENT [Internet]. 2022 Mar. 30; 3 (2): 10-6. Available from: https://ejdent.org/index.php/ejdent/article/view/167

Odovtos -Int J Dent Sc endoses to CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Odovtos -Int J Dent Sc endoses to CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0.