Borucan Social Cohesion: Maternity, Allomaternity with Breastfeeding up until Puberty

Keilyn Rodrígues-Sánchez1 & Javier Tapia Balladares2

1 Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR), Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas (CIAN), San José, Costa Rica; keilyn.rodriguez@ucr.ac.cr; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8397-4630

2 Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR), Instituto de Investigaciones Psicológicas (IIP), San José, Costa Rica; https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6499-4898

July-December 2025, 35(2)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.15517/8p89xw27

Received: 01-11-2024 / Accepted: 28-06-2025

Revista del Laboratorio de Etnología María Eugenia Bozzoli Vargas

Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas (CIAN), Universidad de Costa Rica (UCR)

ISSN 2215-356X

Abstract: This article presents an ethnographic study on the practice and social function of co-maternity and breastfeeding among the Boruca, an indigenous group. We find these practices are possible due to a network of reciprocal relationships between related women and their children. These practices give older women access to companionship and affection and increase care and attention when they reach old age. Meanwhile, young allomothers receive an orientation to motherhood as they care for their siblings. This tradition ensures that a mother’s youngest child has a privileged place in the family while their siblings are cared for by allomothers. We show that cooperative breeding and allomaternal breastfeeding practices reinforce social integration and that these practices, that include breastfeeding up until puberty, promote cultural resistance through maternal and intergenerational family members. Thus, maternal practices have supported cultural identity in an ethnicity that has continuously been exposed to diverse influences.

Keywords: prolonged breastfeeding; indigenous childhood; human breeding; co-maternity; social cohesion.

Cohesión social boruca: maternidad, comaternidad con lactancia incluso hasta la pubertad

Resumen: Este artículo ofrece una etnografía sobre la práctica y la función social de la co-maternidad y el amamantamiento entre los borucas, un pueblo indígena. Encontramos que estas prácticas son posibles gracias a una red de relaciones recíprocas entre mujeres y con sus niños. Estas prácticas proveen a las adultas mayores de compañía, afecto, cuidado y atención. Mientras que las alomadres jóvenes reciben orientación sobre maternidad en el momento que cuidan de sus hermanos. Esta tradición asegura que el hijo menor tenga un lugar privilegiado en la familia, mientras sus hermanos son cuidados por co-madres. Mostramos que la crianza cooperativa y el amamantamiento alomaterno refuerzan la integración social e incluyen el amamantamiento inclusive hasta la pubertad, promoviendo la resistencia cultural por medio de estas prácticas familiares, maternas e intergeneracionales. Así, a través de esta concepción de la maternidad se promueve la identidad cultural étnica, la cual ha estado continuamente expuesta a diversas influencias.

Palabras clave: amamantamiento prolongado; infancia indígena; co-maternidad; crianza humana; cohesión social.

Introduction

Breastfeeding is more than feeding, it is a framework for development of other behaviors. Fouts et al. (2012), Meehan et al. (2012) and Dettwiler (1988) found that as a developmental goal of various cultural forms of breastfeeding are related to the proximity of the child to the group in the aka, Bofi foragers, Ngandu, and Bofi farmers (African tribes). Also, congruent with the expected developmental goals of the proximal groups, Yousi et al. (2003) conclude that an important characteristic is frequency and duration of breastfeeding until weaning.

Following Fouts et al. (2012) and Yousi et al. (2003), we show that co-motherhood and late breastfeeding are family strategies that go together and promote the social cohesion of the individual with the women of their family and therefore, with their cultural identity. The ethnographic report employed in this study aims to systematize the meaning and practice of prolonged breastfeeding in the Borucan children within the context of co-maternity (Figure 1). The term ‘prolonged breastfeeding’ is being used to describe a practice that has not been discussed in academic literature for the communities under study. Though earlier reports only uncovered breastfeeding until 7 years of age, this practice consists of suckling until puberty in specific cases related to co-maternity (Rodríguez y Tapia, 2019).

The meaning and the practice of breastfeeding is culturally variable according to the socialization goals that coincide with the introduction of children to social life (Yovsi & Keller, 2003). An example is the existence of milk kinship and the presence of allomaternal nursing in approximately half of all registered world populations, where female filiation is favored when breastfeeding (Hewlett et al. 2014).

It has also been reported that breastfeeding induces a response between the mother and the child in brain regions implicated in bonding (increased oxytocin production), favoring the development of empathy and maternal sensitivity (Bartlett, 2005; Kim et al., 2011; Pilyoung et al., 2011).

The Borucas begin to breastfeed their children at birth. Due to the trust the primary investigator (PI) had built with the Borucas over the past twenty years, some Borucan women revealed that in many cases, breastfeeding continues until puberty. It is important to note that, in this article, the word ‘breast feed’ will be used to describe suckling at the breast without necessarily implying that suckling includes lactation. In other words, the Borucan women use their breasts to not only feed their children, not only, but also as a pacifier, so that their children may suck on a breast without necessarily feeding.

Cooperative Breeding and Allomaternal Care

In societies that practice child rearing among several mothers, the introduction of the baby to the social world is mediated by cultural activities performed by this caregiving (Hrdy, 2007; Kramer, 2009). For Boruca, we show that allomothers are typically women from the maternal family who also nurse children.

Cooperative breeding provides information on the history of human life, sociality, human psychology, and the way humans could and can survive in times of scarcity. In this way, human cooperative processes occur within the context of subsistence where the exchange of food is a necessary requirement involved in the cost of bearing and raising children. This provides support allowing for more children (i.e. Meehan et al., 2012) with a higher level of care. Also, cooperative breeding research has made it possible to understand the high demographic patterns in societies with limited economic resources (Kramer. 2010; Kramer et al., 2015; Turke, 1988).

The degree of kinship is a central criterion in the identification of those individuals who assist in childcare. This could be other women in the family, the current couple, or their other children. Proximity of residence is also used as a way to locate a co-mother. As will be shown for the case of Boruca, a co-mother is usually an adolescent or an older woman so allomaternal care doesn’t impact their own reproduction (Hrdy, 2007, 2009a. 2009b; Kramer, 2010, 2014; Meehan, 2005; Scelza et al., 2019).

In addition to the evolutionary, economic and population benefits, Burkart et al. (2009) and Ruffman et al. (1998) point out that in co-maternal societies an increase in the cognitive performance of the subjects is evidenced as a collateral effect. They point out that children who grow up with several mothers develop social intelligence, social tolerance and spontaneous pro-sociality. Children must learn to attend to different demands and relationships associated with their close maternal bonds.

All of these aspects have been observed among the Boruca. The unique practice of prolonging breastfeeding until puberty can be added to socially cohesive allomaternal behaviors.

The Boruca of Costa Rica

Borucans have been exposed to diverse and constant external cultural pressures since the mid-17th century. During the Colonial Period, the Spanish created a single diminished territory or reduction in which the Quepo, Borucaca, Coto, Turucaca and Abubae indigenous groups were relocated. In the mid-17th century, this reduction was placed ‘under the guardianship’ of Franciscans who founded the pueblo of ‘Concepción de Boruca’, today known as Boruca (Rodríguez, 1995). Different ethnic groups were forced to form a single town where they were evangelized by Franciscans and quickly lost much of their mythology and language.

The initial town, Concepción de Boruca, was located on a commercial route called ‘Camino de Mulas’. This route was active for centuries and was traveled commercially by many people from different cultures, including Boruca. This has allowed them to be exposed to different cultural influences, and together with the evangelization processes has led to a great loss of traditional culture and yet it is a group that defines itself as indigenous and maintains its ethnocultural particularities.

Currently, the indigenous people of this reduction are known as the Boruca of Coast Rica. The current population is around 2500 individuals distributed into two large communities in the southern portion of Costa Rica: Boruca and Rey Curré, as well as dispersed in the areas surrounding these communities. Though Spanish is the language spoken by this group, they continue to use some terms derived from their ancestral Borucan language, part of the Chibchan language group.

The Boruca kinship system was defined by Stone (1949) as matrilineal. However, the paternal role has now been redefined by the influence of the dominant system. Currently, it consists of a mixed system, including elements like matrilocality, that continue to be prevalent in their daily lives.

Boruca and Rey Curré are rural communities centered around agriculture, cultural tourism and arts and crafts. Most women specialize in textile manufacture while the men mainly focus on mask production. Regardless, women have begun entering the production processes of mask making. These crafts among others have a broad commercial network of production and distribution, both nationally and internationally. The Borucan mask has an evolution that demonstrates their maintenance of traditional manufacture while adjusting to market demand. An example being the production of the ecological mask design as a product of market demand (Campos Chavarría, 2018).

The Boruca are known within Costa Rica for their masks related to the annual rite of los diablitos. This ritualizes the encounter between the Boruca (los diablitos, for not being baptized) and the bull (the Spanish). At the end of three days of struggle, the winners are los diablitos of Boruca. There is also a children’s version of the rite that occurs after the adult ritual, introducing the children to male traditions. This reinforces cultural identity through a constant memorial of the perceived struggle and victory against conquest (Campos Chavarría, 2018; Rodríguez, 1995). In the same sense, the female practice is socially cohesive and binds children to matrilineal networks of relatives through the temporally prolonged ritual of breastfeeding.

Boruca and Rey Curré have access to diverse public services: drinking water, electricity, telephone lines, satellite access television, internet, primary and secondary education, a community museum, a community center, a public healthcare center (known as EBAIS), and access to public transit infrastructure. Situated within the Territorio Indígena Brunka de Brunca, both towns include rural non-Indigenous families among their residents. Each has an Asociación de Desarrollo, which serves as its legal representative before the Costa Rican state.

At the moment, the work of Williams (1976) is the only record we have found on infant breastfeeding related to Boruca. The author solely refers to breastfeeding up to 3 or 4 years of age. Nevertheless, he does not delve further into this topic as it was not the central theme of his article.

We consider prolonged breastfeeding as a tradition because the older members of the community recall the practice as having occurred in the past, and that it had occurred more frequently.

Investigation Procedure

This investigation consisted of a thematic ethnographic study (Angrosino, 2012) with complementary techniques (censuses, group investigations, focal groups). The field work was done from February 2016 until December 2018. During this time, we visited the site 20 times with stays that varied from 3 to 4 days. The PI performed participant observation while staying with lactating mothers who practiced prolonged breastfeeding or allomaternal care. During these visits, 26 ethnographic interviews (informal conversations) were performed and recorded in a field journal the same day that they occurred. Also, 21 thematic interviews with mothers and grandmothers were audibly recorded and transcribed into text and reported in the field journal. During the interviews, children and other members of the family occasionally joined in the discussions. It is important to mention that a distinction is made in the data between the information recorded through informal interviews and that which represents the audio transcriptions.

Every participant in this study provided informed consent for the use of their commentary. All participants can read and write in Spanish.

We performed a census in the primary schools, Escuela Líder Doris Stone and Escuela de Rey Curré, to determine the quantity and the ages of the children who were breastfeeding as well as grade during the period under investigation. This allowed us to verify the validity and importance of the practice within the Borucan families in each community. The census was performed using written response, made anonymous for children in cycles I and II (equivalent to a primary school’s 1st to 3rd, 4th to 6th grades). A direct response was obtained privately in an open space, one on one, for those children in preschool who could not yet read or write. In each school, we worked through two consecutive days to complete each census. There was a four-month gap between the census performed at each school. The question asked of each student was whether they suckled at or played with their mothers’ breasts at bedtime. If the answer was affirmative, we assumed they were in the process of weaning.

Additionally, among the complimentary techniques used were conversational group interviews to corroborate the information, analyze interpretations, and share results. This was done in two moments. During the first year of field work in Boruca, three interviews were done with groups of between two and six women. Later, in 2017 we implemented seven focal groups in which men and women participated in groups between four and twenty people. Additionally, we participated in a radio program with a Borucan who interviewed the PI and transmitted it via Radio Boruca.

This ethnography was executed in Spanish, as this is the language they currently speak. It was translated with the help of fellow anthropologist Dr. Scott Hergenrother, a native English speaker.

The analysis of the data was done using grounded theory through the software Atlas Ti. The interviews and field journal were coded to establish families of codes, only for one level, due to the descriptive interest of the study. Table 1 shows the details.

The construction of the codes and the families was done using the collected information and considered the categories used by the informants. In the references of the interviews, brackets were used to introduce commentaries, clarifications, or name substitutions when there is reason for privacy. Similarly, anything that could negatively impact the dignity or the identity of the individuals that contributed to the investigation was omitted without altering the results of the analysis of the presented data.

Results

The family Context of Parenting

Family socialization is the cultural mechanism of initial enculturation of an infant. Through the process of guided participation (Rogoff, 2003), activities with culturally defined meaning are designed to favor the teaching-learning of the children according to the demands and development goals useful and valued by different cultures.

The upbringing of the children is organized by the culture through familial pedagogy. This occurs though language, objects with cultural meaning, collectively constructed spaces, forms of familial relationships including allomothers, and a series of sequential activities according to developmental level and socialization goals, like breastfeeding. The family is what introduces the children to social life.

In Boruca and Rey Curré, it’s common for women to have children from different fathers; moreover, the mother’s current boyfriend or husband is often not the biological father of all her children. Of all the families the PI has encountered over the past 20 years, there was only one case in which the current husband had fathered all the mother’s children. This situation does not generate discrimination because they are all specifically from the mother’s family.

It is necessary to clarify that, within the Borucas, we find two types of maternity connected to breastfeeding. Primary maternity begins with pregnancy and goes on until the weaning of the child. Secondary maternity begins after weaning and continues for the rest of their life. Primary maternity is more valued than secondary maternity. This will be further clarified later in the article.

In the case of first-time mothers, they allow themselves to be guided and taught, through what we previously referred to as guided participation. They are taught by their mother on selfcare and childcare during pregnancy, birth, and afterwards. This is most intensive with the mother’s first child, where her mother is controlling and must forcefully be obeyed. This is taken in context with the age of first birth occurring between 14-17 years of age.

It is possible for the first-time mother to live with her mother until she is in a serious relationship or decides to live on her own. In this way, the first months or years of a relationship may be spent with the mother’s mother, until the new mother learns what is necessary to formalize a relationship and can live in her own house. This matrilocality allows the grandmother to breastfeed with her eldest daughter and at least her first-born, particularly if the mother studies, works, or leaves to do chores or sporadic work. We observed an example of this in one of the families where the PI was staying. The grandmother had her eldest daughter and her children staying with her for multiple years. This was the case until the daughter had a stable partner and subsequently moved to her own house in the land next to her mother’s. This allowed the grandmother to breastfeed her eldest grandchildren—who call her ‘mommy [mami]’, while they called their mother by her name (cooperative breeding and allomaternal care). Additionally, this family had an older daughter who also lived with her mother, grandmother, and great grandmother. Similarly, the second daughter lived with her mother for multiple years after having her first son. In all three cases, the grandmothers had breastfed their first grandchildren (Notes from field journal, February 6, 2016). This allowed the grandmothers’ motherhood to be greatly prolonged, allowing them to wean their youngest children while continuing to breastfeed their grandchildren.

However, when a daughter decides to have her own house, it is usually constructed near her mother’s or near the maternal grandmother’s house. The children that grow up in, or around the grandmother’s house are also breastfed by her and call her mother, and they may call their own mother the same, or by her name. This is what indicates the presence of matrilocality (Stone, 1949). Obviously, it is possible to find exceptions. Although exceptions exist. Women who do not have a family, are not Borucan, or who inherit land from their father have been observed, indicating that it is possible to encounter couples living in different localities.

In addition to the maternal side of the extended family, another aspect that facilitates breastfeeding of the grandchildren is when they are the same age as the other children being breastfed by the maternal grandmother. This also occurs with the mother’s sisters.

In this way, the responsibilities of motherhood and upbringing of children are shared intergenerationally. The first-time mother follows direction and accepts supervision and help from her mother, while she continues learning and assuming responsibility for her subsequent children. A Borucan mother explained she, as well as her brother, called their grandmother mami, the Spanish word for “mother” because she had breastfed them (Notes from field journal, July 30, 2018). This is related to cooperative breeding and allomaternal care.

When does the process of delegating maternal roles to a daughter begin and end? It is not clear that it ever ends, as the authority of the maternal grandmother is sustained by the love of the eldest grandchildren until her grandchildren are adults. Perhaps longer?

The youngest daughter’s youngest child does not always benefit from double maternity as the woman may not be lactating when her grandchildren are born. Regardless, in some cases, the aunts and older sisters of the child can occupy a co-maternal role, adopting breastfeeding and a caregiving responsibility for life.

This situation allows an intergenerational network of care for the children that we call cooperative breeding, where a woman can maintain and prolong her primary maternity (with dependent children through prolonged breastfeeding) until the second or third generation with the children of her oldest daughter or daughters. At the same time, children call her ´mother´. This functions as a primary motherhood upgrade that plays a central role in the femininity of Borucan women. Further on, we will discuss in detail the link to that primary motherhood. We do not act as if this is a universal category, but it helps us to understand the function of prolonged breastfeeding in Boruca.

It is usual that the current youngest child sleeps in the bed with their mother or allomother. Because of this, many years may go by while the father or boyfriend sleeps on a couch next to the bed. This can last for 5 or more years. If the couple wants to have sexual relations or intimacy, the mother will leave the bed while the child sleeps. Many fathers have noted that they know that the baby or child needs the warmth of their mother more than they themselves do; therefore, they are happy to give them that space (Notes from focal group, July 20, 2017).

When the child gets to a certain age, if the mother is in a relationship, the sleeping arrangement may change. In this case they use a small bed, like a crib without guardrails, which is placed between the couple’s bed and the wall. The child will sleep there, in a social space that serves as an intermediate between their mother’s bed and their siblings’ room. On the other hand, a first-time mother that has been single for many years may wish to continue sleeping with her youngest child and prolong breastfeeding until the next child is born. This was the first case of prolonged breastfeeding that the PI encountered in Boruca. In this case, the mother had, in confidence, commented that she was breastfeeding her 10-year-old daughter.

In this sense, at a time when the investigation was being explained to a Borucan woman, she said, “The woman binds the children of different men. The men leave their children in different families” (Notes from the field journal, May 20, 2016).

In summary, we have discussed how matrilocality and family play a central role in motherhood of Borucan women, due to the connection between relationship stability and emotional security. To understand the family system and the upbringing of the children in Boruca, it is necessary to understand that they live together, in the same space. In this way, maternity and sharing is intergenerational and not individualistic. The elderly women prolong their primary maternity through their grandchildren, while the children provide companionship and emotional support.

Prolonged Breastfeeding

As was mentioned earlier, maternity and breastfeeding of Borucan infants is a cultural value related to femininity. Here we will focus on the practice of cooperative breeding of allomaternity and breastfeeding children up to puberty. In some cases, allomaternity can evolve into co-maternity, wherein the child identifies not one, but two maternal figures. Therefore, allomaternity refers to instances in which a woman provides occasional support to another—such as through breastfeeding—without establishing a maternal co-parenting bond with the child (Kramer, 2005; Rodríguez-Sánchez & Hergenrother, 2025).

In Boruca, it is the youngest child of each family that participates in prolonged breastfeeding. This period of prolonged breastfeeding occurs from the age of 4, until weaning, which may extend until puberty. When the children are infants, they are breastfed continuously. However, as they grow, they drink less breastmilk (if any) until they are only breastfeeding once or twice a day and before going to sleep at night. Production of breast milk may cease if there is little consistency between breastfeeding sessions and if the mother is not feeding another child. If this is the case, this does not stop the child from sucking at the breast of their mother as if it is a pacifier. Co-maternity can sometimes greatly extend the period that a child is breastfed.

During the sessions of prolonged breastfeeding, the child and the mother cuddle. The child usually plays with the mother’s nipples, smells her breasts, and suckles. The mother speaks using motherese (baby talk), sings, and reads to the child, according to whatever the pair decides. These sessions continue during a late nap (see Figure 2) and at night during bedtime.

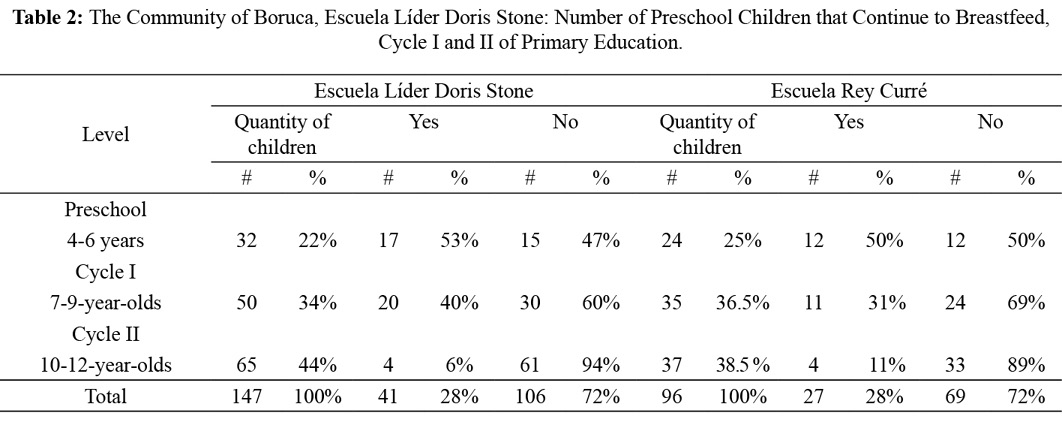

Based on the results of the census we performed in the two schools in Boruca and Rey Curré, we consider prolonged breastfeeding a current cultural practice. See the details in the following Table 2.

Because only a woman’s youngest child is breastfed, the data presented should not be interpreted as a function of all children. In this context, we can understand that the children of Cycle II (ages 10-12) that are breastfeeding—8 in total, 4 from each school—are the youngest. We can infer that the older a child, the more likely they are to have a younger sibling.

It is important to mention that there is a taboo against breastfeeding two siblings at the same time. They believe that both children will be ‘ruined’ (will get sick and not develop well), and that because of this it should not happen. That is different for allomaternal breastfeeding. In Boruca, any child can be breastfed by two women of the maternal family. But a single woman should not breastfeed two children without assistance and should never breastfeed siblings. It is important to mention that the rule for twins has yet to be uncovered.

The Youngest Child’s Place

The children that can be breastfed until puberty are specifically the youngest of any group of siblings. A child can continue to be breastfed until the mother has her next child.

The difference in bond that develops between the mother and the youngest child and the mother and the rest of her children is evident. Regardless, another woman in the family can breastfeed the other children without regard to age, forming a similar maternal bond. We continue by analyzing the characteristics of the bond that develops between the mother or allomother and the child being breastfed.

Pampering or ‘Chineo’

The youngest child is the most pampered (chineado) or spoiled in the family, while the other children can still be breastfed by allomothers. Although the mother or maternal caregiver is the most active in the chineo, the entire family participates. The youngest may stop being pampered by their biological mother at the moment that they have another sibling. The mother’s focus then changes to the newborn child.

A child can be pampered until a sibling is born. They may also stop being pampered because everybody knows that another child is on the way. In this case, another woman may begin to pamper the child forming a strong allomaternal bond.

Equally, a child may erroneously be considered the mother’s last and eventually she has another. In these cases, we have seen that the bond between the second to last child and the mother is maintained as if they were the youngest, even though that is not the case. Resentment is generated between the youngest and second youngest sibling. This is the case with informant (p. 26, mother), who commented:

“…when my mother became pregnant with the one that followed me, I did not want to know anything about it. Like a little girl, I said, “What a shame, I don’t want her, nor do I want to play with her or anything!’ because I was jealous like that…

…In fact, I don’t get al.ong with that sister….”

A 13-year-old boy approached while the PI was talking with his mother and said in an annoyed voice that if his brother had not been born then he would be the one breastfeeding (Note from the field journal, February 4, 2016).

The minors actively demand and assume the role of being the most privileged. They expect exclusive privileges from the family. They expect their mother to ensure that they receive gifts and other privileges. Resentment of the penultimate sibling due to lost privileges is not directed toward the mother (authority) but towards the youngest sibling.

The exclusive and ideal form of pampering a child is to breastfeed him until the child wants to stop, provided that this does not continue into puberty. One of the mothers whose youngest child died in an accident said: “But I have that, that, that good thing that I know that among all of them, he was the one who suckled the most. That it was, I don’t know, I had a thing about him that… that he was very pampered.” (p. 31, mother and grandmother)

With those heartfelt words, the mother reflects on how, at least she is left with the knowledge that her deceased child was the one who suckled the most, and therefore was very pampered. This goes on to further solidify the cultural importance of this practice, and how it closely correlates with their views on maternal love.

The act of pampering a young child gives an impression of overprotection on the caregiver’s part because they are never, not in the least, poorly treated, and always and in everything have preference and priority. It is not permissible to scold or bother them until they cry because they are considered the king or queen of the house, the most intelligent and the most beautiful. One of the informants recounted:

…a boy was born and he was nursed for the longest time, which was different from my sisters who had to go and cut rice from the time they were six and had to sell milk from the same age. The favorite son [the youngest] couldn’t leave the mountain because he was the king of the house (p. 27, mother and grandmother).

The youngest never work equally as hard as their older siblings. A young girl, the youngest in the house, reported that she inherited the house from her mother and her only task was to position a stick, so that the hens could get up and sleep in their tree. That was her sole daily responsibility, while the rest of her siblings were assigned more demanding tasks.

The Duty of the Youngest and the Right of Inheritance

There is an expectation that the mother’s youngest child will care for her in old age and will support her economically. Because of this, it is a tradition for the youngest to inherit his mother’s or parents’ house and everything on the property. According to the granddaughter of one the older grandmothers, while accompanying the PI back from interviewing the old woman, commented: “It’s that, for example, my grandmother just said that she didn’t have a preference and that all of her children were equal. But that [name], the youngest son that breastfed until he was 9, will get the house.” (Notes from the field journal, Abril 11, 2016, p. 7, mother).

The Right to Possess the Mother’s or Caretaker’s Breasts

The mother’s or caretaker’s breasts are considered to be the youngest child. The child knows this and does not share with their siblings, cousins, or anyone. A child has the right to throw a fit if anyone tries to touch them. One of the mothers commented:

[the youngest children] say ’My boobs’ [Implying they own them] … it’s not that anyone told them that; they make them theirs…. If someone else tells them that they are going to breastfeed or ‘I want to touch it’, the child does not allow it. It is her property [the youngest daughter’s]. … I cannot tell her to stop breastfeeding (p. 26, mother and grandmother).

The meaning of the breasts needs to be understood in the context of connection: to sleep with the mother, to have this privileged space to talk, to be the preferred, to be king. If another child tries to occupy the mother’s breasts, the privileged space has been usurped, and because of this, the role of the youngest child is lost. Effectively, the place of the youngest son or daughter can be usurped by a cousin, especially when growing up, getting married and leaving the house to live with their partner.

During one visit, a girl, approximately 5 years of age, was crying because she could no longer breastfeed. There was a newborn brother. Her mom came over to comfort her and let her suck on the side of her breast to comfort her and help her cope with her grief. She was in mourning for having lost her mother’s breasts. In this case there was no allomother.

‘Attached’

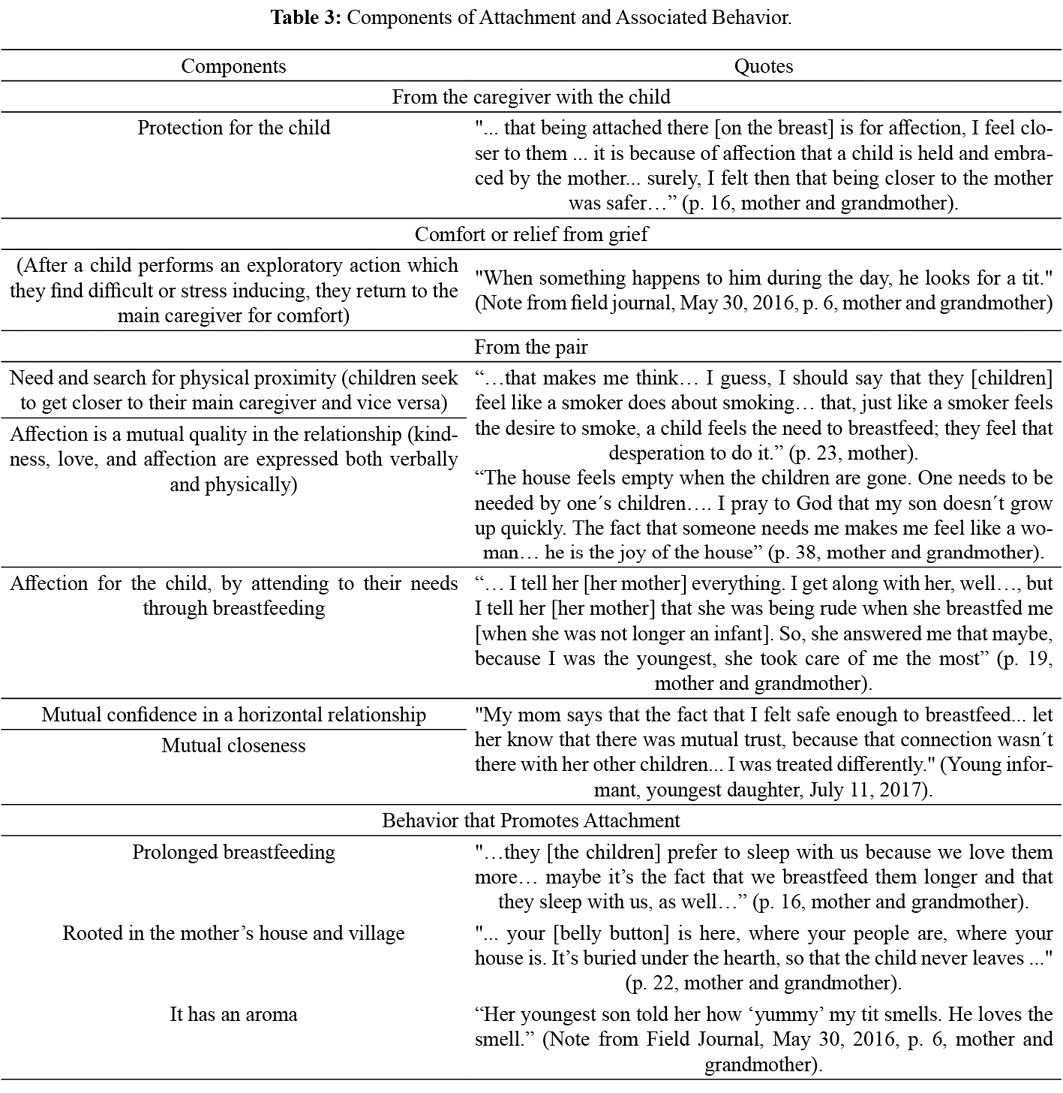

When the mothers discuss the reasons why they breastfeed their children for so long, they usually say that it is due to their attachment to the child. Exploring this category from a cultural perspective, we found the following components (see Table 3).

Three major aspects should be noted from the table above. First, reciprocity is implicit in the late breastfeeding relationship between mothers and children. Second, the individual’s attachment to their group; the informants say that Borucas always return home. Recently two cases generated these comments about the return of the Boruca. In one, a prominent Boruca who had worked in an international organization in Europe retired and returned. In the other, an elderly brother of several community leaders was living in the United States. With their help among other recourses, he was able to collect money to move back home. This attachment to family is a form of social cohesion that links members to their families and therefore to the Borucan people.

Prolonged Allomaternal Breastfeeding

Allomaternal breastfeeding occurs in the Boruca. In the case of prolonged breastfeeding, it is also possible that a woman who is not the biological mother may build a close connection with the child. This can happen for multiple reasons:

• In general, it can be used as a tactic to wean children who have a new younger sibling that is being breastfed. They are brought to the house of their maternal aunt, older sister, or maternal grandmother so that they do not suffer from the consequent distancing from their biological mother. The children will sleep in both households while only being breastfed in the household of the maternal relative until the child is fully weaned.

• When the mother needs to leave the house frequently, the child can be breastfed by two women (always family) simultaneously.

• When a child suffers for any reason outside the norm: illness, abuse, the death of someone close.

Through these practices a maternal bond can be created with another woman. It is important to note that the prolonged breastfeeding of a child with a non-familial woman has not been reported. Previous studies have already described the preference for selecting the allomothers by kinship first and by residence second (Hrdy, 2009a, Hrdy, 2009b; Kramer, 2010, 2014; see Table 4).

Breast milk is shared because the children belong to the women of the tightly knit maternal family. If a woman has not maintained close ties to their family, they do not participate in allomaternal practices. Co-motherhood of children is reinforced through the network of intergenerational reciprocity between women of a family.

Self-Determination and Social Pressure: Weaning and Prolonged Breastfeeding

Upon asking informants how they wean the young they commonly say “…he did it by himself.” (p. 17, mother and grandmother). Similarly, a young 22-year-old woman said that: “When they weaned me at 7 years of age, mommy didn’t do it because she wanted to, but because I was super embarrassed. I was going to school, and I was afraid that my classmates would find out. Mostly because I thought that I was the only one still suckling…” (p. 14, July 11, 2017).

The previous quote also shows the social pressure experienced by the youngest siblings to decide ‘autonomously’ to stop breastfeeding. What appears to be happening is that the social pressure created by both their peers and the older children is generating a fear of being embarrassed. It is the possibility of social punishment that sways the child, like that which causes the child to decide to quit breastfeeding. During a stay with a family, a Borucan mother asked her son when he was going to stop breastfeeding, and he said that he would stop ‘next summer’. After the next summer had passed, the 10-year-old was still breastfeeding. The mother asked again, and he again replied, ‘next summer’. (Notes from the field journal, February 4, 2016, and March 6, 2017). It seems that breastfeeding for so many years makes it difficult to quit.

The decision to stop breastfeeding has another component that they call ‘el olvido’ or forgetting to breastfeed. It is interesting that this, in appearance, is a contrast to self-determination; although, for them it is a complimentary idea. It is one thing to forget, while it is another altogether to decide to stop doing something. So, a young child can decide to stop breastfeeding because ‘they forgot’; that is, because they are no longer accustomed to the act.

‘Forgetting’ can be promoted by the mother by having her child occasionally sleep with their siblings or visit their grandmother, until the child is frequently falling asleep without their mother while forgetting or not needing to breastfeed. Prolonged breastfeeding is promoted by the co-sleeping arrangement between the youngest child and the mother. In this case, eliminating this arrangement is a form of weaning. In one of the sessions where results were shared with the community, a mother approached me and said that her youngest daughter was in preschool, but even if this seemed to be in the distant future, she was certain she would die if a day went by without nursing her daughter. She could not imagine sleeping without her (Note from Field Journal, July 21, 2017).

The co-sleeping-breastfeeding relationship was corroborated in the interviews with the mothers. If the youngest child slept with the mother, they were always being breastfed. Due to this relationship, an indirect technique of weaning is using social pressure to eliminate co-sleeping. Another weaning technique related to social pressure consists of making fun of the ‘big boy’ who breastfeeds. When asking one of the grandmothers (p. 24, mother, grandmother and great-grandmother) how she was able to get her son to stop, she responded: “Eh… because they teased him a lot, like… his siblings. They teased him saying that he was disgusting [cochino] and drank and drank from the boob while he was such a big boy, and that is how he stopped.”

The expression cochino means ‘disgusting’, and it is used because he is doing something that he should not; at his age it is disgusting to breastfeed. The weaning conflict is again transferred to the siblings, not to the mothers. The conflict is not with the authority figure.

Weaning has a double cost; both for the child who needs to make the decision to stop breastfeeding, as well as for the mother who needs to stop sleeping with and breastfeeding her youngest child.

Mothering a child that is breastfeeding is different than motherhood for a non-breastfeeding child or adult. A child that breastfeeds is affectively dependent. When they stop breastfeeding, they are made independent. Although the mother continues cooking and doing housework for everyone, with the youngest the relationship is stronger. A mother (p. 36) commented on independence; “Something happens when weaning; they become independent… she doesn’t look for me now… she sleeps by herself.”

In the reference above, the tone of the affirmation has a dose of nostalgia. Feeling the need for a physical and emotional connection that came with sleeping together and being looked for to breastfeed is what is missed. This feeling usually coincides with menopause. During a stay in a house, performing participant observations, the following was recorded:

A 10-year-old boy said that he gave up the boob. But, after a couple of weeks during which his mother went to San Jose for two days and upon her return to the house, she asked the boy to breastfeed. So, the child asked his mother in front of me, ‘Do you want me to keep breastfeeding?’ The mother didn’t respond, she only placed her hands on his face and gave a warm nod (Field Journal, note from October 26, 2016, p. 40, mother and grandmother).

We can note with that example that the mother also needs the boy. The feeling is mutual as one of the informants expresses: “… it is needed by my son and by me to be with my son. It is like when you talk to yourself.” (p. 36, mother and grandmother.)

Other informants call this type of feeling apego or attachment and they describe it in diverse ways that show the quality and care of the relationship. For example: “And there they [mother and child] are comforted, snuggled…for hours … and we talk” (p. 38, mother and grandmother).

The relational interaction between the mother and her youngest child may offer the mother feelings of satisfaction and fulfillment. Perhaps the bond creates a feeling of security during menopause, old age, and other moments in which the relationship makes the mother feel needy, useful, loved, and in a relationship with mutual benefit. In this way, a strong bond is established between the mother and the child. For the youngest child, the feeling of importance over all the other siblings and grandchildren is central, being more valued and loved than them, and having a safe place in their family and town. The conflict is between the siblings and not with the women or older women who represent the tradition of the group, the authority.

Mutual Benefits and Social Implications

In Boruca, prolonged breastfeeding involves benefits for both the mother and the youngest child, apart from those medical and psychological benefits previously reported (Rodríguez & Tapia. 2019). The following table (Table 5) outlines the benefits of prolonged breastfeeding for the youngest child.

Complications are also created due to the prolongation of the youngest children’s infancy, as they may be mocked by their peers. As an example, during a trip to the community, the youngest child in a house, a 10-year-old, did not want to go to school. Speaking with his mother, I was informed of an incident that had occurred the day before. He had taken his stuffed animals with him to school to hide them from his mother, and his classmates had made fun of him for having them at his age (Note from Field Journal, March 6, 2017). On the other hand, the mother also benefits from breastfeeding for so many years. As demonstrated below in Table 6.

Through breastfeeding her children, the mother or allomother receives affection and security by investing so much time, day after day, year after year. This investment increases the likelihood that she will be cared for in her old age. After all, the child invests the same amount of time as his or her mother. This time also increases the bond between children and their mother, and subsequently, children and their allomother.

Intergenerational cohesion is maternally reinforced. For example, the allomaternal elders represent the cultural knowledge of the group. They share their expertise related to having and raising Borucan children. They are privy to Borucan language terms that are not directly translatable into Spanish, and that coexist with the Spanish spoken by the group. They share stories surrounding Boruca as well as knowledge pertaining to their own traditions and many other mysteries not shared with si’kuas (outsiders). Thus, strong intergenerationally bonded familial networks are supported through maternal and allomaternal practices.

Discussion

Guided participation (Rogoff, 2003) as a family-based didactic strategy for allomaternity and prolonged breastfeeding promotes a strong reciprocal bond within the network of women participating in intergenerational cooperative breeding and between the children and their caregivers that spans generations. Due to this practice within the same family, a network of bonds is created spanning from a woman’s grandmother all the way through to her granddaughter. These bonds promote intergenerational social cohesion that includes and is strengthened by strong biological components through mechanisms like the extended release of oxytocin due to the prolonged period of breastfeeding (PBarlett, 2005; ilyoung et al., 2011). The physical-biological, emotional and economic ties function to strengthen cultural cohesion.

We propose that social cohesion reinforces intergenerational resistance, guarding against various cultural influences that they have been exposed to since the mid-17th century. Keeping the practice of breastfeeding till puberty private has made it possible to resist outside influence and pressure from other cultures while maintaining a sense of identity.

Hèau Lambert (2007) referred to the term of cultural resistance to mean the everyday tactics and strategies used by the indigenous people to confront the de-indigenization which is promoted by the official culture. These tactics, conscious or not, can be used as security valves that avoid the dismantling of the community. These persistent cultural practices are united through hidden infra-political discourse. This is how we see prolonged breastfeeding. Until now, it has been a discourse and a practice that has been both persistent and hidden in one of Costa Rica’s most studied indigenous groups. It has been a security valve that did not permit the disintegration of the social group, articulated by the breast of the maternal family. This is in harmony with what was demonstrated by Yousi et al. (2003) which associated the frequency of breastfeeding with the proximity of the group. We conclude that cohesion is a tactic of cultural resistance, which allows the biological and cultural reproduction of the group.

This appears to be resistance to historical attempts at colonization and neo-colonization, as well as against the influence of the homogenizing effect of globalization, as the exemplified by transformation of the Boruca mask and the ritual of los diablitos.

Prolonged breastfeeding is a cooperative, reciprocal, familial and communal practice. It strengthens the bond between the child and their caregivers, and therefore with the cultural group as a whole. The bond is physical, close, affectionate, placental; socially, highly valued and with an implicit economic feeling of reciprocity as the youngest, most esteemed, child inherits the house and its land from their parents, but also cares for them in their old age, just as women contribute to the raising the children. Moreover, it demonstrates a developmental goal that strengthens the closest possible proximity of the child to the group, as reported by Yousi and Keller (2003). This bond with the caretakers allows the child a sense of belonging (My mother’s breasts belong to me, and I belong to them) in concordance with Nash´s point of view, “The primary beliefs and rituals constitute the deepest roots in sense of identity in people.” (1988, p. 115) like burying the umbilical cord in the earth under the hearth and nursing children for years.

Women in Boruca are guaranteed stable company and affection during menopause, in addition to care and support during old age. They spend most of their lives pregnant, breastfeeding or caring for their descendants, while at the same time they are laborers that economically support their families. This daily investment in relationships gives them power, respect, affection, care, and status over their descendants as cooperative breeding, with the hope that their children will return to them and thus the community. For men, this is different and requires another study. This is because their old age is usually more solitary.

Lastly, it is necessary to suggest that the presence of allomaternal nursing can be considered an example of the existence of milk kinship (Hewlett & Winn, 2014), especially when there is a possible co-maternal bond being formed during the process of prolonged breastfeeding. Therefore, this would be a new kind of milk kinship. One that possesses the capacity to reassign and redefine the role of the female relatives of the mother. Thus, it is in such manner that a grandmother or aunt may be dubbed mami, which effectively redefines their place in matrilineal kinship. And consequently, the children forge stronger connections with their mother’s side of the family and the social cohesion is reinforced.

Acknowledgment

This article is the result of the project ‘B5350 Contacto vital: significado y prácticas de amamantamiento entre los Borucas de Costa Rica’ by the Centro de Investigaciones Antropológicas of the Vicerrectoría de Investigación at the Universidad de Costa Rica. Special thanks to Ph.D. Scott Hergenrother and Gloriana Sobrado Rodríguez for the translation to English. This translation aims to retain the original tone and register in Spanish of the source text and interviews. My gratitude to Ph.D María E. Bozzoli Professor Emeritus at the Universidad de Costa Rica and Ph.D Anita Herzfeld (RIP) Professor Emeritus at the University of Kansas.

References

Angrosino, M. (2012). Etnografía y observación participante en Investigación Cualitativa. Ediciones Morata/Sage.

Bartlett, A. (2005). Maternal sexuality and breastfeeding. Sex Education, 5(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/146818142000301894

Burkart, J. M., Hrdy, S. B., & Van Schaik, C. P. (2009). Cooperative breeding and human cognitive evolution. Evolutionary Anthropology Issues News and Reviews, 18(5), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.20222

Campos Chavarría, P. (2018). La máscara: transformación económica, social y cultural en la comunidad indígena de Boruca (1979-2017). [Master’s thesis]. Universidad de Costa Rica.

Dettwiler, K. (1988). More than nutrition: breastfeeding in urban Bali. Medical Anthropology Quarterly, 2 (2), 172–183. https://doi.org/10.1525/maq.1988.2.2.02a00060

Fouts, H.N., Hewlett, B.S., & Lamb, M.E. (2012). A biocultural aproach to Breastfeeding interactions in Central Africa. American Anthropologyst, 114(1), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1433.2011.01401.x

Gómez Meléndez, A., González Evora, F., García, H., Espinoza, M., & Solano Monge, F. (2014). Atlas de los territorios indígenas de Costa Rica. Universidad de Costa Rica. https://hdl.handle.net/10669/15088

Hèau Lambert, C. (2007). Resistencia y/o revolución. Teoría Política, 1 (2), 55-72. https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2007-81102007000100003

Hewlett, B. S., & Winn, S. (2014). Allomaternal nursing in humans. Current Anthropology, 55(2), 200–229. https://doi.org/10.1086/675657

Hrdy, S. B. (2009a). Allomothers across Species, across Cultures, and through Time. In G. Bentley & R. Mace (Eds.), Substitute parents: Biological and social perspectives on alloparenting in human societies (pp. xi–xviii). Berghahn Books. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781845459536-003

Hrdy, S.B. (2009b). Mothers and others: The evolutionary origins of mutual understanding. Harvard University Press.

Hrdy, S.B. (2007). Evolutionary context of human development: The cooperative breeding Model. In C. A. Salmon & T. K. Shackelford (Eds.), Family relationships: An evolutionary perspective (pp. 39–68). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195320510.003.0003

Kramer, K.L., & Otárola-Castillo, E. (2015). When mothers need others: The impact of hominin life history evolution on cooperative breeding. Journal of human evolution, 84, 16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.01.009

Kramer, K. L. (2014). Why what juveniles do matters in the evolution of cooperative breeding. Human nature, 25(1), 49-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-013-9189-5

Kramer, K. L. (2010). Cooperative breeding and its significance to the demographic success of humans. Annual Review of Anthropology, 39, 417-436. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.105054

Kramer, K. L. (2009). Does it take a family to raise a child? Cooperative breeding and the contributions of Maya siblings, parents and older adults in raising children. In G. Bentley & R. Mace (Eds.), Substitute parents: Biological and social perspectives on alloparenting in human societies (pp. 77-99). Berghahn Books. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781845459536-003

Kramer, K. L. (2005). Children’s help and the pace of reproduction: Cooperative breeding in humans. Evolutionary Anthropology, 14(6), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1002/evan.20082

Meehan, C. L., Quinlan, R., & Malcom, C. D. (2012). Cooperative breeding and maternal energy expenditure among aka foragers. American Journal of Human Biology, 25(1), 42–57. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.22336

Meehan, C. L. (2005). The effects of residential locality on parental and alloparental investment among the Aka foragers of the central African Republic. Human Nature, 16(1), 58–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-005-1007-2

Nash, J. (1988). Resistencia cultural y conciencia de clase en las comunidades de las minas de estaño de Bolivia. La palabra y el hombre, 68, 115-132. http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/2084

Kim, P., Feldman, R., Mayes, L. C., Eicher, V., Thompson, N., Leckman, J. F., & Swain, J. E. (2011). Breastfeeding, brain activation to own infant cry, and maternal sensitivity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(8), 907–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02406.x

Rodríguez-Sánchez, K., & Hergenrother, S. (2025). La crianza cooperativa en la especie humana: un enfoque biosociocultural. Cuadernos de Antropología, 23(1) 1-27. https://doi.org/10.15517/cat.v35i1.57254

Rodríguez, K., y Tapia, J. (2019). La lactancia humana como práctica biopsicocultural. Cuadernos de Antropología, 29(1), 1-37. https://doi.org/10.15517/cat.v1i1.34090

Rodríguez Sánchez, K. (1995). La tormenta y el arco iris: significado de la utilización de tintes naturales en la artesanía boruca. [Bachelor’s thesis]. Universidad de Costa Rica.

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

Ruffman, T., Perner, J., Naito, M., Parkin, L., & Clements, W. A. (1998). Older (but not younger) siblings facilitate false belief understanding. Developmental Psychology, 34(1), 161–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.1.161

Scelza, B. A., & Hinde, K. (2019). Crucial contributions: A Biocultural Study of Grandmothering During the Perinatal Period. Human Nature, 30(4), 371–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-019-09356-2

Stone, D. Z. (1949). The Boruca of Costa Rica. Papers of the Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology, XXVI (2). https://peabody.harvard.edu/publications/boruca-costa-rica

Williams, A. R. (1976). Boruca Burucac: An indian village of Costa Rica. Pitzer College Claremont.

Yovsi, R. D., & Keller, H. (2003). Breastfeeding: an adaptive process. Ethos, 31(2), 147–171. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.2003.31.2.147

Author contributions (CRediT)

K. Rodríguez-Sánchez: conceptualization; data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, software, visualization, writing – review & editing.

J. Tapia Balladares: discussion of results, final document review.