Computer or Paper-Based Delivery Mode: An Analysis for Testing English Reading Strategies

Papel y lápiz o por computadora: un análisis para la evaluación de estrategias de lectura en inglés

Mag. Alejandro Fallas Godinez

Université Laval, Québec, Canada

jose-alejandro.fallas-godinez.1@ulaval.ca

ORCID: 0000-0002-9767-3126

Mag. Walter Araya Garita

Universidad de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica

ORCID: 0000-0002-5340-6384

Abstract

This study aims to examine the comparability of scores on the Reading Comprehension Exam (EDI for its acronym in Spanish) with institutional multiple-choice items in two administration modes, namely paper-based tests and computer-based tests, taken by first-year Costa Rican students from different majors at the University of Costa Rica, Costa Rica. The analysis considered both types of administration by comparing test performance and conducting item differential analysis (DIF) among 1145 students during February 2023. Findings revealed that differences between both administration modes are minimal and weak. Furthermore, when differences, they indicate a slight advantage of computer-based over paper-based administration. This study exemplifies how to leverage computer-based testing without adversely affecting candidates by adapting a measurement instrument from paper to digital format.

Keywords: Testing, Language, Reading, Assessment, Paper, Computer

Resumen

Este estudio tiene como objetivo examinar la comparabilidad de las puntuaciones del Examen de Comprensión de Lectura (EDI) con ítems de opción múltiple institucionales en dos métodos de prueba, es decir, pruebas en papel y pruebas basadas en computadora, tomadas por estudiantes costarricenses de primer año de diferentes carreras en la Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica. El análisis abordó los dos tipos de aplicación mediante la comparación del desempeño en la prueba y el funcionamiento diferencial de los ítems (DIF por sus siglas en inglés), en 1145 estudiantes, durante el mes de febrero del año 2023. Los hallazgos revelaron que las diferencias entre ambos tipos de aplicación son mínimas y débiles. Además, dichas diferencias muestran una pequeña ventaja de la prueba en computadora sobre la aplicación en papel. Este estudio ejemplifica cómo aprovechar las pruebas en computadora sin afectar a los candidatos al adaptar un instrumento de medición de papel al formato digital.

Palabras Clave: Evaluación, Lengua, Lectura, Papel, Computadora

Introduction

Lately, multiple assessment tools have migrated to computer-based delivery mode. Therefore, a need to guarantee fair assessment tools requires investigating the impact of adapting a paper-based test into a computer-based one. A test can be considered fair when it “reflects the same construct(s) for all test takers, and scores from it have the same meaning for all individuals in the intended population” (American Educational Research Association et al., 2014, p. 50). Therefore, fair tests should yield equivalent results regardless of their delivery mode. Despite the differences in both delivery modes, evidence has also suggested that it is possible to measure the same construct using both delivery modes (Brunfaut et al., 2018; Chua, 2012; Jiao & Wang, 2010; Jin & Yan, 2017; Kunnan & Carr, 2017; Yeom & Henry, 2020), without a significant impact on final test scores.

Traditional paper-based testing (PBT) has long been used to assess individuals’ knowledge and skills. Notwithstanding, advances in technology have introduced new forms of test administration. For instance, CBT has become increasingly common due to its convenience. Moreover, CBT is gaining recognition as a tool that can provide valuable insights into the instructional needs of test takers, enhancing student engagement (Yu & Iwashita, 2021). Nonetheless, possible threats to score comparability can still arise, as pointed out in Kolen (1999), and the literature still presents inconclusive results, as researchers have found mixed evidence regarding the differences between PBT and CBT in general (Brunfaut et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2003; Chua, 2012; Coniam, 2006; Guapacha, 2022; Kunnan & Carr, 2017; Jiao & Wang, 2010; Yeom & Henry, 2020; Yu & Iwashita, 2021), making it difficult to reach a complete consensus.

Assessing Reading

It is a must to define the concepts of reading comprehension and reading strategies to provide a foundational understanding of the cognitive and linguistic processes involved in effective reading. Tajuddin and Mohamad (2019) conceptualize reading comprehension as a multifaceted cognitive process that extends beyond basic word recognition. It involves not only deciphering individual word meanings but also constructing an understanding of the broader context in which these words are situated. Comprehension, therefore, requires advanced cognitive and linguistic abilities to integrate knowledge, maintain textual coherence, and parse information effectively. Proficient readers can grasp both literal and inferential meanings, facilitating deeper engagement with the text. Operationally, Tajuddin and Mohamad (2019) assess comprehension through participants’ performance on multiple-choice questions based on narrative and expository texts, thereby measuring their capacity to recall, interpret, and apply information drawn from their reading experience (p. 9).

Beyond reading comprehension, reading strategies are defined by Harida (2016) as deliberate techniques and cognitive processes that readers employ to support comprehension and engage meaningfully with a text. These strategies enable learners to systematically process a text, extract relevant information, and construct meaning beyond the literal level. Critical reading strategies, an advanced subset of these techniques, promote higher-order thinking skills by encouraging readers to analyze, evaluate, and synthesize information (Harida, 2016, p. 204). Moreover, Harida (2016) emphasizes that reading strategies can serve as valuable tools for assessing students’ reading comprehension. Traditional forms of assessment may not fully capture the depth of students’ understanding; thus, integrating critical reading strategies—such as identifying the author’s purpose, distinguishing between facts and opinions, drawing inferences, and evaluating tone and bias—into the assessment process provides a more authentic and comprehensive evaluation of reading proficiency (Harida, 2016, pp. 200–204).

Computer-Based Testing (CBT)

The integration of multimedia and interactive features in CBT has transformed the test-taking experience. Yeom and Henry (2020) highlight practicality from traditional PBT. Main differences lie in the ability of CBT to provide immediate scoring and reports, enhance test security, allow for efficient and flexible test administration, reduce costs and incorporate innovative multimedia items (Wang et al. 2008, p. 6), leading to simulated experiences where students can respond to and interact with as reported in Araya and Acosta (2022). The integration of multimedia in CBT can take various forms, such as audio clips, videos, animations, and interactive diagrams. This multimedia content can be used to present information in a more engaging and dynamic way compared to static text and images typically found in PBT. This interactive nature of CBT can lead to a more engaging and immersive test-taking experience for students (Araya-Garita, 2021). It allows them to actively participate in the testing process, rather than passively answering questions. This active engagement can lead to deeper understanding and better retention of information. Moreover, the use of multimedia in CBT can cater to different learning styles. While some students may prefer reading text, others may learn better through visual or auditory content. By offering a variety of content types, CBT can provide a more inclusive and personalized testing experience.

Another key advantage of CBT is the ability to deliver immediate feedback, enhancing learning opportunities during the testing process. The interactive nature of CBT allows for immediate feedback. Students can be informed right away if their answer is correct or not, and in some cases, they can even receive hints or explanations (Araya-Garita, 2021). This immediate feedback can be a powerful tool for learning, as it allows students to identify and correct their mistakes promptly. However, the implementation of multimedia in CBT is not without challenges. It requires significant resources, including advanced technology and skilled personnel to create and maintain the multimedia content. There may also be issues related to accessibility and technical glitches. In other words, careful planning, resource allocation, and ongoing support to ensure equitable and reliable implementation can guarantee its success.

Beyond enhancing student experience, CBT also serves as a valuable tool for instructors to analyze and improve instructional practices. Some authors such as Anakwe (2008) and Tajuddin and Mohamad (2019) agree that one of the ways it does this is by allowing instructors to monitor the distribution of time students spend answering questions. In a traditional classroom setting, it can be challenging for instructors to keep track of the time spent answering each student’s questions. However, in a CBT environment, this process can be automated and streamlined. The computer-based system can log the time spent by students on each question, providing a clear picture of where students are facing difficulties. This data can be incredibly useful for instructors. For instance, if an instructor notices that a significant amount of time is being spent on a particular topic, it could indicate that students are finding this topic challenging. This could prompt the instructor to review their teaching methods for this topic, provide additional resources, or even re-teach the topic if necessary.

More recently, Wei (2025) highlights that with the growth of online education platforms, integrating computer-based reading comprehension tests (CBTs) has become essential for assessing students’ reading skills and providing timely feedback. However, the author notes that many existing CBT models are homogeneous, inefficient in question selection and assembly, and offer low accuracy in ability estimation. To address these limitations, Wei (2025) suggests using hybrid computer-adaptive multistage tests (CA-MST) based on Rasch measurement theory, which dynamically matches test items to learners’ abilities, reduces test length, and improves precision. The model leverages advanced statistical techniques, such as deviation entropy and fuzzy hierarchical analysis, to quantify item difficulty and enhance item bank quality, achieving superior test efficiency (98%) and more accurate ability estimates compared to traditional CBTs. Ultimately, Wei (2025) positions traditional CBTs as valuable but limited tools, advocating for hybrid adaptive CBTs as a more effective solution for scalable, accurate, and user-friendly English reading comprehension assessment in online education.

Previous Studies on Computer-Based Language Testing

This section briefly discusses the key facets explored in the comparison between PBT and CBT. Studies in language testing have explored the comparability of PBT and CBT in aspects such as general performance (Brunfaut et al. 2018; Chan et al., 2018; Choi et al., 2003; Hosseini et al., 2014; Kunnan & Carr, 2017; Yeom & Henry, 2020), cognitive processes (Chan et al., 2018; Guapacha Chamorro, 2022; Yeom & Henry, 2020; Yu & Iwashita, 2021), test takers’ perceptions (Brunfaut et al. 2018; Guapacha Chamorro, 2022; Yeom & Henry, 2020) and speed (Tajuddin & Mohamad, 2019). This shows how the adaptation of PBT into CBT is a complex process that involves different variables. A gap emerges when considering that most of the previous studies have been conducted in Asian contexts (Choi et al., 2003; Coniam, 2006; Jin & Yan, 2017; Kunnan & Carr, 2017; Tajuddin & Mohamad, 2019; Yeom & Henry, 2020; Yu & Iwashita, 2021), while research in Latin Ame~rica remains scarce (e.g. Guapacha Chamorro, 2022).

In language assessment, different macroskills have been compared under both modalities, with reading (Choi et al., 2003; Hosseini et al., 2014; Jiao & Wang, 2010; Kunnan & Carr, 2017; Tajuddin & Mohamad, 2019; Yeom & Henry, 2020; Yu & Iwashita, 2021) and writing (Brunfaut et al., 2018; Chan et al., 2018; Guapacha Chamorro, 2022; Jin & Yan, 2017; Kunnan & Carr, 2017; Yu & Iwashita, 2021) receiving more attention than listening skills (Coniam, 2006; Yu & Iwashita, 2021). This may be attributed to the test tasks but also the comparative ease of adapting reading and writing assessment instruments into CBT. Specifically on reading, research still shows conflicting results. For instance, no significant differences in performance have been reported (Chan et al., 2018; Jiao & Wan, 2010; Tajuddin & Mohamad, 2019; Yeom & Henry, 2020), contrasting reported higher scores in the PBT (Hosseini et al., 2014). Similarly, while some participants have shown stronger preference for the CBT (Hosseini et al., 2014), some others still prefer PBT (Yeom & Henry, 2020). Also, Tajuddin and Mohamad (2019) reported that reading was significantly faster in the PBT mode. At an item level, Jiao and Wang’s (2010) study yielded minimal differential item functioning (DIF) and parallel structures supported by a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) across administration. In regard to cognitive processing, Yeom and Henry (2020) found differences in two reading strategies: keyword unknown word marking. Though limited, these examples only highlight the need for more empirical research to substantiate the claim that CBT is entirely equivalent to PBT, leaving aside the practical advantages discussed earlier.

Computer-Based Testing in Costa Rica: The Experience of PELEx

CBT can influence different types of engagement, thereby providing a comprehensive understanding of a student’s instructional needs. In the context of the Program of Language Assessment at the University of Costa Rica, PELEx, CBT has been introduced as a novel approach for conducting examinations (Araya-Garita, 2021), reporting positive attitudes about the suitability of using a computer-based English test. However, different challenges related to infrastructure have been found in different applications. This feedback can be used to improve the conduct of the examination and the overall learning experience. Moreover, the implementation of CBT requires careful consideration of various factors. These include the assumptions and beliefs of stakeholders about computer-based instruction and assessments, the system as a whole, the computer or online platform, the specific accessibility features of CBT, and the policies for which accessibility features will be available to all students. By considering these factors, educators can ensure that CBT is implemented in a way that meets the instructional needs of all students.

To illustrate what is happening in Costa Rica, it is necessary to describe PELEx. The Assessment and Training Program in Foreign Languages (PELEx), based at the School of Modern Languages at the University of Costa Rica (UCR), is a leading initiative in the conceptualization, development, and administration of large-scale online language proficiency assessments in Costa Rica and the broader Latin American region. PELEx plays a pivotal role in providing valid and reliable language assessments that support national education policy and promote linguistic competence. Since 2019, the program has strategically transitioned its tests to online formats to address disparities in digital infrastructure across Costa Rican public high schools, thereby improving accessibility and standardization (O’Sullivan, 2016). Leveraging over three decades of expertise in assessment design, PELEx now develops and delivers tests in five languages—English, French, Portuguese, Italian, and German. A flagship product of the program, the Prueba Diagnóstica de Lengua Inglesa (PDL) is an online English assessment developed for diagnostic and placement purposes, following the framework described by Brown and Abeywickrama (2019), and aligned with the national CEFR-referenced curriculum. To date, PELEx has assessed more than 500,000 individuals through its diverse suite of instruments.

PELEx has also faced some drawbacks of CBT assessment. Based on PELEx’s test administration experience, some students after taking such computerized tests often complain that their test score is not the real representative of their language proficiency because of their unfamiliarity with such test modes (Araya-Garita, 2021). Despite the use of computer in language learning, the examinations are still conducted in the traditional form, i.e. paper-based format in different educational contexts in Costa Rica, even during and after the COVID 19 pandemic. However, as institutions started to accomplish CBT in their examination systems along with traditional PBT systems, concerns like those in Kolen (1999) arose about the comparability of scores from the two administration modes. For Hosseini et al (2014),

as the computerized tests have been used for almost 20 years, and the computer assisted language learning (CALL) has been common since the middle of 20th century, it has been necessary to develop the means to include computerized tests. They also asserted that the mismatch between the mode of learning and assessment could cause achievement to be inaccurately estimated. (p. 2)

Although CBT offers many advantages over traditional PBT as previously mentioned, equivalency of scores between the two test administration modes has been the real concern for the researchers and experts in the area of assessment, practitioners, and educators (Lottridge et al., 2008). While Computer-Based Testing (CBT) presents opportunities for enhancing language assessment through greater accessibility, efficiency, and engagement, its implementation is not without challenges. The experience of PELEx highlights both the potential and the complexities of adopting CBT in contexts with varying levels of digital readiness and test-taker familiarity. There are some other issues related to score comparability, test mode effects, and stakeholder perceptions must be carefully addressed to ensure fair and valid assessment outcomes. Moving forward, continuous research, stakeholder training, and thoughtful integration of CBT alongside traditional formats will be essential to optimizing its use in language assessment practices across Costa Rica and similar educational contexts.

Methodology

This study only focused on the difference between PBT and CBT. Therefore, it was based on a post-positivism world view where data and evidence shape knowledge (Creswell & Creswell, 2018). Accordingly, this study employed a quantitative approach, as detailed below.

Research Objective

The main objective of this study was to highlight possible differences in an English reading strategies test when being administered in two different modalities: a paper-based (PBT) or a computer-based (CBT) administration. Accordingly, the research null hypothesis was H0: There is no difference between the computer and paper-based delivery modes in the English reading strategies test.

Sample and Data Collection

This study considers 1 145 out of 1 901 first-year undergraduate students (nearly 60% of the tested population) from the English Diagnostic Test in 2023, at the University of Costa Rica, in Costa Rica. Participants were randomly assigned to perform the test virtually or paper-based. Candidates took the test the same day at the same time.

For CBT takers, participants were assigned to a computer laboratory equipped with desktops or laptops. Participants were restricted from opening other tabs in their browser. Participants performed the test using the PELEx virtual platform. Answers were reported immediately after being sent, and participants were not able to change their previous answers once they had submitted them.

For PBT takers, participants were assigned to regular classrooms. Test takers needed to fill out an optical answer sheet. The test materials constituted a booklet with the test questions, the optical answer sheet, and the reading. Tests were checked using an optical mark recognition device.

For both scenarios, participants were allotted an equal duration to complete the test. In both test administrations, test takers were allowed to use a paper English dictionary or Spanish-English dictionary. Electronic devices were not allowed in any of the administrations, as part of the test protocol.

Instrument

PELEx administers the English Diagnostic Exam (EDI) for first-year students at the University of Costa Rica (UCR) based on its internal regulations since 2009. The application of this exam has been one of the measures that the institution has taken to address the unmet demand in the course LM-1030 Reading Strategies in English I. Similarly, according to the regulations of the University of Costa Rica, students who pass this exam have the possibility to request the School of Modern Languages (ELM) the equivalence of the course LM-1030 and the grade obtained in the test, which is the one that appears in the student’s academic record, does not affect the weighted average of student enrollment. Therefore, following the specifications of the course program, reading skills for this test were defined as a variety of reading strategies that would allow users to participate actively and logically in the construction of reading material, at the same time, they can understand and analyze such texts by taking a subjective position considering the author’s perspective. (Programa de Evaluación en Lenguas Extranjeras, n.d., p.1)

Then, nine Target Language Use (TLU) domains were covered in the test:

- Reading for the main idea

- Reading for major points

- Reading for specific details

- Reading for the gist, inferencing, predicting, skimming, scanning,

- Determining the meaning of unfamiliar vocabulary from context

- Distinguishing facts from opinions

- Sensitizing to rhetorical organization and to cohesion of the text

- Identifying the author’s purpose or tone

- Paraphrasing a text (Programa de Evaluación en Lenguas Extranjeras, n.d., p.2)

For both administrations, the previous TLU domains were distributed into 52 multiple-choice items with two distractors and one correct answer. To complete the test tasks, test takers used a complete text at a B2+ or C1 level according to CEFR based on test specifications (Programa de Evaluación en Lenguas Extranjeras, n.d.). To ensure the language level of the text, PELEx employed the Persons’ text analyzer available in the GSE Teacher Toolkit (Pearson, n.d.). The main difference between both administrations was the structural presentation of the test input, also known as the stimulus. In the PBT, the stimulus was presented as a complete text, whereas in the CBT, the stimulus consisted of selected excerpts from the full text. Nonetheless, in PBT instructions, test takers were provided with the paragraph and page number to complete the test task.

Data Analysis

As referred before, this study used a quantitative approach for analyzing the instrument at two levels of measurement. The former level aimed to analyze the item performance based on Differential Item Functioning (DIF). Although multiple methods of estimation have been studied and used for DIF analysis (Bechger & Maris, 2015; Chen et al. 2024; Magis et al., 2022; Martínez et al., 2014), this study compared the results of only three DIF methods. To cover Classical Test Theory and Item Response Theory methods, this study compared the logistic regression (Swaminathan & Rogers, 1990), Lord’s chi-square test (Lord, 1980), Raju’s area (Raju, 1990) results, aiming to underline differences between PBT and CBT.

The latter level of measurement sought to compare the performance of the two testing modes by means of the general test’s reliability and final performance. Focusing on the Classical Test Theory where test scores are the result of all items, this second level compared the distribution of the final grades and the internal consistency of each administration mode. For this, Cronbach’s alphas and a Mann-Whitney U test were used. The statistical analyses were done using R, version 4.3.1 (R Core Team, 2023).

Results

Results from this study highlight differences between the delivery mode at an item level, but the general performance seems invariable. In the item level, DIF analysis support showed a difference among 9 out of 52 items. Table 1 summarizes the differences regarding the three methods. In this item analysis, most of the differences favor CBT participants rather than PBT.

Table 1

Number of DIF Items Classified by Group with Better Performance

|

Method |

Total |

Group |

|

|

Computer |

Paper |

||

|

Logistic Regression |

7 |

3 |

3 |

|

IRT Model: Raju |

9 |

6 |

3 |

|

IRT Model: Lord |

9 |

6 |

3 |

Note. English Diagnostic Test 2023, PELEx.

Stronger differences benefited CBT. Three out of six items benefiting the CBT group belonged to exercises regarding word building. For these exercises, students were requested to identify the morphological nature of a word by recognizing suffixes, prefixes, and compound words. Figure 1 shows the item with the most prominent difference. In this case, the probability of answering this question increases for those who took the CBT. Similar results were given by the Lord and generalized logistic models.

Figure 1

Item Characteristic Curve. Item 21. IRT Model: Raju

Note. Reference group = CTB, Focal group = PBT.

English Diagnostic Test 2023, PELEx.

Contrarily to the previous case, only three items were flagged with differences benefiting PBT mode. In this case, two of them responded to exercises about implicit and explicit information. To complete these exercises, applicants were asked to recognize if the information provided was implicitly or explicitly presented in a section of the text. Figure 2 shows how PBT had higher chances to answer the item, compared to CBT participants. Under this scenario, test takers who took the PBT had more probability of correctly answering this item.

Figure 2

Item Characteristic Curve. Item 47. IRTModel: Raju

Note. Reference group = CTB, Focal group = PBT.

English Diagnostic Test 2023, PELEx.

As seen above, differences arose at an item level. However, general performance suggests consistency in the test results. At a performance level, the CBT mode shows a slightly more consistent level, higher Cronbach’s alpha, than the paper-based delivery mode. In this case, CBT showed a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.82 with a standard error of measurement (SEM) of 6.15. For the PBT, Cronbach’s alpha slightly decreases to 0.81 with a SEM of 6.2. Despite the small differences, these results demonstrate consistency in the measurement of this test in the context of its adaptation from PBT to CBT. Consistency coefficients and SEMs show similar values across both administrations.

Table 2

Descriptive Statistics by Type of Test Administration

|

Administration |

n |

Min |

Median |

Mean |

Max |

SD |

|

Total |

1145 |

10 |

28 |

29.09 |

50 |

7.57 |

|

Paper-based |

337 |

14 |

28 |

28.92 |

50 |

7.48 |

|

Computer-based |

808 |

10 |

28 |

29.16 |

49 |

7.61 |

Note. English Diagnostic Test 2023, PELEx.

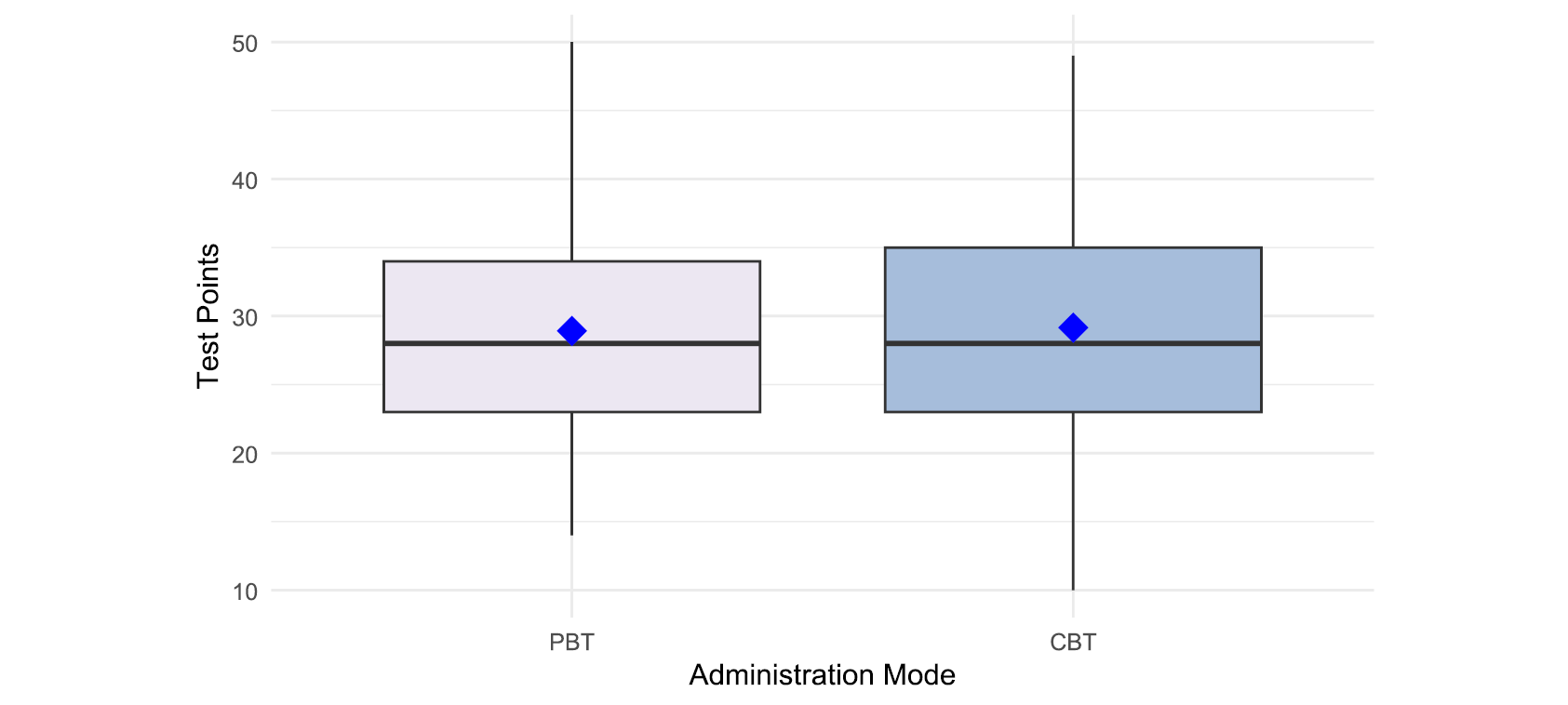

Comparing students’ performance, both test administrations share similar means and medians with similar standard deviations (see Table 2). Due to the lack of normality (W = 0.98, p-value < 0.001), the final performance of both groups was compared using a non-parametric method. Figure 3 graphically shows the distribution of students’ grades in the test for both administration types.

Figure 3

Distribution of Test Scores and Means by Type of Test Administration

Note. English Diagnostic Test 2023, PELEx.

As expected, the final performance of test takers did not show statistical differences. Test results did not reject the null hypothesis of no differences between administration modes (W = 133469, p-value = 0.6).

Discussion

Results at item and test scores levels from this study mainly support the adaptation of PBT into CBT with few differences. At an item level, a comparison of DIF analysis identified those items with differences between test delivery modes. Then, at a performance level, final grades underlined little difference between both delivery modes.

For the DIF analysis, the three methods were consistent for underlining differences in the item performance: logic model (Swaminathan & Rogers, 1990), Lord’s chi-square test (Lord, 1980), Raju’s area (Raju, 1990). Although some differences are appreciated, these represent a low percentage of the total items, being consistent with Jiao & Wang (2010). Therefore, it becomes clear that the adaptation of PBT into CBT is possible with a minimal impact on candidates’ performance.

Despite variations at the individual item level, the candidates’ overall performance remained consistent. This observation becomes evident when we compare the consistency levels of the assessment instruments (measured by Cronbach’s alphas and SEM) and consider the candidates’ aggregate performance. While item level analyses suggest a slight advantage for CBT over PBT as in other skills (Choi et al., 2003; Jin & Yan, 2017; Kunnan & Carr, 2017), the impact on candidates was minimal. It is essential to recognize that no adaptation can perfectly align both administration types. Therefore, differences from the stem adaptation may arise rather than the delivery mode, which should not also impose a threat on items’ difficulty, discrimination, or construct representation as discussed in Kolen (1999).

Results from this study are consistent with previous studies on language testing (Brunfaut, 2018; Chan et al., 2018; Guapacha Chamorro, 2022; Tajuddin & Mohamad, 2019; Yeom & Henry, 2020; Yu & Iwashita, 2021) where no general difference between CBT and PBT were found. However, it is important to highlight the advantages discussed when using CBT. First, CBT often provides instant feedback (Araya-Garita, 2021), allowing students to understand their performance right away. This immediate response can motivate students to engage more deeply with the material and strive for improvement. Its flexibility is another important asset as discussed in Wang et al. (2008). CBT can be taken at any time and from anywhere, making it more convenient for students. This flexibility can reduce test-related stress and allow students to perform at their best, thereby promoting engagement. Likewise, many CBT systems are adaptive as in Coniam’s study (2006), meaning the difficulty level of the questions can be adjusted based on the test-taker’s performance. Moreover, CBT in general can be more engaging (as reported in Brunfaut et al. 2018; Coniam, 2006; Hosseini et al. (2014), while being paperless, it is a more sustainable option compared to traditional paper-based tests. This aspect may engage students and mainly stakeholders who are conscious about environmental issues. Finally, as students move towards a more digitalized world, having experience with CBT can prepare them for future scenarios, as recommended by Yeom and Henry (2020). Thus, as seen in this study, the adaptation of a paper test into a digital one does not necessarily imply detrimental differences among candidates’ test scores.

Future research should explore the implications of construct validation when adapting reading strategies tests including the qualitative approach, particularly for items exhibiting differential item functioning. For example, investigating which TLU domains or cognitive process can demonstrate higher advantages for CBT over PBT could inform modifications to the test’s table of specifications and even the underlying construct itself.

Results from this study supported the use of CBT when assessing reading skills by the English Diagnostic Exam (EDI) at the UCR. The lack of significant differences in the final test scores and only minimal item-level discrepancies between test administration modes provide support for the adoption of computer-based testing for this context. Moreover, considering the ecological benefits of CBT and the technological environment we live in, CBT adoption appears not only justified but also aligned with the 21st century.

References

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing.

Anakwe, B. (2008). Comparison of student performance in paper-based versus computer based testing. Journal of Education for Business, 84(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.3200/joeb.84.1.13-17

Araya-Garita, W. (2021). Dominio lingüístico en inglés en estudiantes de secundaria para el año 2019 en Costa Rica. Revista De Lenguas Modernas, 34, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.15517/rlm.v0i34.43364

Araya, W. & Acosta, A. (2022). The design of the test of English for young learners. Proceedings of the IV English Teaching Congress, 42-52. https://doi.org/10.18845/mct.v28i1.2022

Bechger, T. M., & Maris, G. (2015). A statistical test for differential item pair functioning. Psychometrika, 80, 317-340.

Boo, J., & Vispoel, W. (2012). Computer versus paper-and-pencil assessment of educational development: A comparison of psychometric features and examinee preferences. Psychological Reports, 111(2), 443–460. https://doi.org/10.2466/10.03.11.pr0.111.5.443-460

Brown, H. D., & Abeywickrama, P. (2019). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

Brunfaut, T., Harding, L., & Batty, A. O. (2018). Going online: The effect of mode of delivery on performances and perceptions on an English L2 writing test suite. Assessing Writing, 36, 3-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2018.02.003

Chan, S., Bax, S., & Weir C. (2018). Researching the comparability of paper-based and computer-based delivery in a high-stakes writing test. Assessing Writing, 36, 32-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2018.03.008

Chen, X., Aryadoust, V., & Zhang, W. (2024). A systematic review of differential item functioning in second language assessment. Language Testing, 42(2), 193-222. https://doi.org/10.1177/02655322241290188

Choi, I. C., Kim, K. S., & Boo, J. (2003). Comparability of a paper-based language test and a computer-based language test. Language Testing, 20(3), 295-320. https://doi.org/10.1191/0265532203lt258oa

Chua, Y. P. (2012). Effects of computer-based testing on test performance and testing motivation. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(5), 1580-1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.03.020

Coniam, D. (2006). Evaluating computer-based and paper-based versions of an English-language listening test. ReCALL, 18(2), 193–211, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344006000425

Creswell, J. W. & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). SAGE Publications

Guapacha Chamorro, M. E. (2022). Cognitive validity evidence of computer- and paper-based writing tests and differences in the impact on EFL test-takers in classroom assessment. Assessing Writing, 51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2021.100594

Harida, E. S. (2016). Using critical reading strategies; One way for assessing students’ reading comprehension. Proceedings of ISELT FBS Universitas Negeri Padang, 4(1), 199–206.

Hosseini, M., Abidin, M. J. Z., & Baghdarnia, M. (2014). Comparability of test results of computer based tests (CBT) and paper and pencil tests (PPT) among English language learners in Iran. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 98, 659-667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.03.465

Jiao, H., & Wang, S. (2010). A multifaceted approach to investigating the equivalence of computer-based and paper-and pencil assessments: An example of reading diagnostics. International Journal of Learning Technology, 5(3), 264. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijlt.2010.037307

Jin, Y., & Yan, M. (2017). Computer Literacy and the Construct Validity of a High-Stakes Computer-Based Writing Assessment. Language Assessment Quarterly, 14(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2016.1261293

Kolen, M. J. (1999). Threats to score comparability with applications to performance assessments and computerized adaptive tests. Educational Assessment, 6(2), 73–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326977ea0602_01

Kunnan, A.J., & Carr, N. (2017). A comparability study between the general english proficiency test- advanced and the internet-based test of english as a foreign language. Language Testing in Asia, 7, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-017-0048-x

Lord, F. (1980). Applications of item response theory to practical testing problems. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203056615

Lottridge, S., Nicewander, A., Schulz, M. & Mitzel, H. (2008). Comparability of paper-based and computer-based tests: A review of the methodology. Monterey: Pacific Metrics Corporation.

Magis, D., Béland, S., Tuerlinckx, F. & de Boeck, P. (2010). A general framework and an R package for the detection of dichotomous differential item functioning. Behavior Research Methods, 42, 847–862. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.42.3.847

Martínez, M. R., Hernández, M. J., & Hernández, M. V. (2014). Psicometría. Madrid: Alianza Editorial.

O’Sullivan, B. (2016). Adapting tests to the local context. In New directions in language assessment: JASELE journal special edition (pp. 145-158). Japan Society of English Language Education & the British Council.

Pearson. (n.d.). Text Analyzer – GSE Teacher Toolkit. https://www.english.com/gse/teacher-toolkit/user/textanalyzer

Programa de Evaluación en Lenguas Extranjeras. (n.d). Tabla de especificaciones Examen de Diagnóstico de Inglés (EDI). Archivo.

R Core Team. (2023). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. https://www.R-project.org/

Raju, N. S. (1990). Determining the significance of estimated signed and unsigned areas between two item response functions. Applied Psychological Measurement, 14, 197-207. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662169001400208

Swaminathan, H., & Rogers, H. J. (1990). Detecting differential item functioning using logistic regression procedures. Journal of Educational Measurement, 27(4), 361–370.

Tajuddin, E. S., & Mohamad, F. S. (2019). Paper versus screen: Impact on reading comprehension and speed. Indonesian Journal of Education Methods Development, 3(2). https://doi.org/10.21070/ijemd.v3i2.20

Wang, S., Jiao, H., Young, M. J., Brooks, T., & Olson, J. (2008). Comparability of computer-based and paper-and-pencil testing in k-12 reading assessments: A meta-analysis of testing mode effects. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 68(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164407305592

Wei, Y. (2025). Building an adaptive test model for English reading comprehension in the context of online education. Service Oriented Computing and Applications, 19(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11761-024-00395-x

Yeom, S., & Henry, J. (2020). Young Korean EFL learners’ reading and test taking strategies in a paper and a computer-based reading comprehension tests. Language Assessment Quarterly, 17(3), 282-299. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434303.2020.1731753

Yu, W., & Iwashita, N. (2021). Comparison of test performance on paper-based testing (PBT) and computer-based testing (CBT) by English-majored undergraduate students in China. Language Testing in Asia, 11, 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-021-00147-0