Abstract

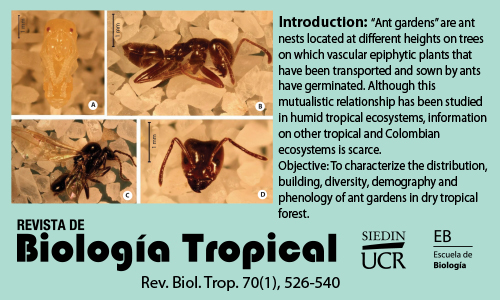

Introduction: Ant gardens are ant nests located at different heights on trees on which vascular epiphytic plants that have been transported and sown by ants have germinated. Although this mutualistic relationship has been studied in humid tropical ecosystems, information on other tropical and Colombian ecosystems is scarce. Objective: To characterize the spatial distribution, formation process, diversity, demography, and phenology of Ant gardens in a secondary dry premontane transitional forest in Colombia. Methods: We estimated the spatial distribution and formation process of ant gardens. Phenological and demographic monitoring of epiphytes plants of ant gardens was performed. The monitoring of the ant gardens was done in transects, every 15 days. Results: The ant gardens showed an aggregated distribution pattern relative to water bodies. The garden-forming ant species was identified as Azteca ulei. Ten species of epiphytes plants and 13 species of phorophytes trees related to ant gardens were identified. The behavior of A. ulei favored the formation and maintenance of the ant gardens. A positive relationship was found between epiphyte richness and ant garden size. Some epiphytes presented a bimodal phenological pattern. The demographic pattern of epiphytes suggests that in the dry season, the number of established seedlings is reduced, which reduces the number of adults that remain in ant gardens. Conclusions: Ant gardens are the microhabitat that allows the germination, establishment, and reproduction of diverse epiphytes in the studied dry-premontane transitional forest.

##plugins.facebook.comentarios##

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2022 Revista de Biología Tropical